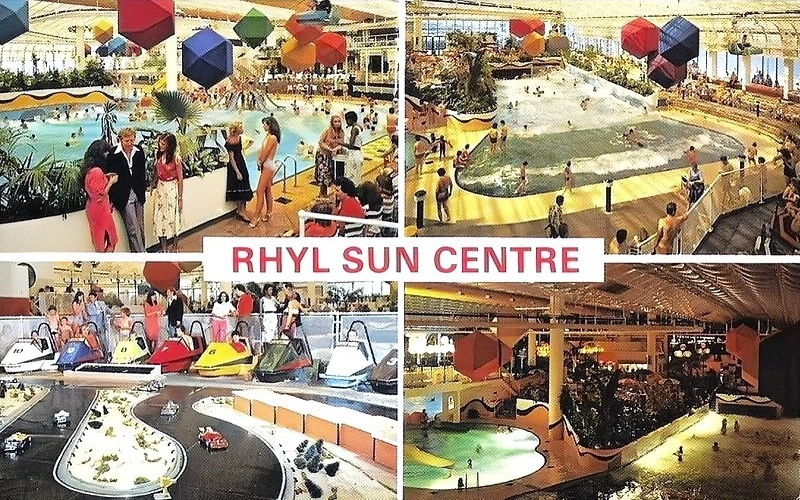

The idea of a seafront monorail at Rhyl was the brainchild of American engineer Alan Hawes. Through his company, Universal Design Limited (UDL), Hawes had been creating theme park attractions in the United States since the 1960s, with projects ranging from observation towers and dark rides to chairlifts and monorails. In Britain, working under his firm AH Design, he was involved in several high-profile leisure projects, including the Butlins monorails at Skegness and Minehead and the chairlifts at Scarborough and Southport. Hawes first became familiar with Rhyl in the late 1970s, when he helped develop the suspended monorail at the town’s new Sun Centre swimming complex.

The £1.5 million Rhyl monorail was conceived not just as a novelty ride, but as a genuine seafront transport system. Stretching 900 metres along the promenade, it was planned to run from the pavilion car park (now the site of the Sky Tower) to the Sun Centre. Alan Hawes agreed to finance the scheme himself, paying the council a rent equivalent to 5% of the gross takings.

Hawes confidently declared that the monorail would “take Rhyl into the 1980s,” while others suggested it could help prevent the resort from “becoming another New Brighton.” The line was originally due to open in time for the 1979 season, but in April that year Hawes announced a year’s postponement, citing financial complications, delays in steel delivery, and last-minute design changes to the track.

To keep the project moving, he proposed building the line in two stages. The first phase, a 460-metre section, would run from the pavilion car park to a station on the site of the old open-air swimming pool (now the Rhyl Events Arena). The council agreed, on the condition that the second half – an additional 470 metres along Marine Parade linking to the Sun Centre – was completed the following year.

At the same time as the Rhyl project, Alan Hawes was also pursuing several other ambitious ventures, including plans for a new amusement park at Marine Lake in Rhyl, a scheme to save and redevelop Brighton’s West Pier, and proposals for another monorail in Scarborough.

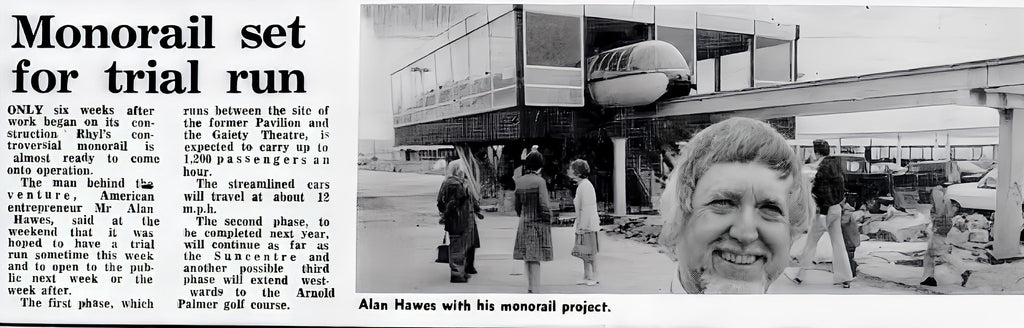

Work on the Rhyl Monorail finally began in April 1980, but construction was not without controversy. Complaints quickly arose over the steel girders being erected along the promenade. One resident remarked: “I think it looks terrible. Rhyl’s wonderful promenade is being ruined.” Practical issues followed, as delivery lorries and even emergency vehicles struggled to pass beneath the structure. The original plans had included a hydraulically raised section to allow vehicle access, but Hawes later suggested it might be simpler to lower part of the promenade instead.

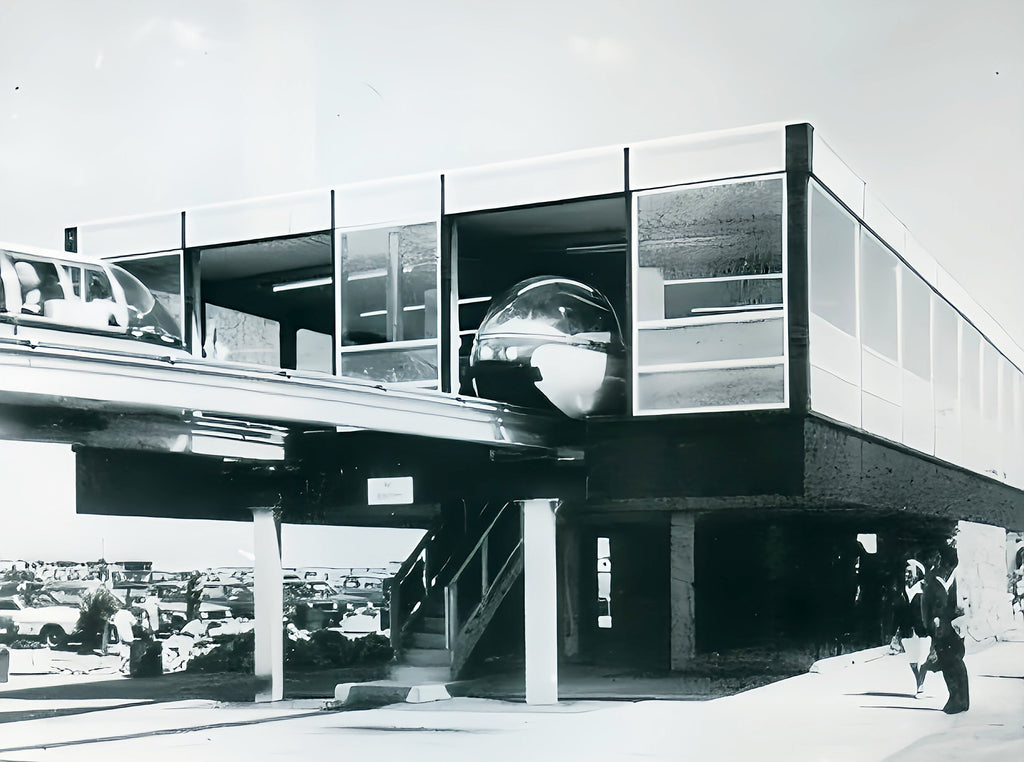

Despite the problems, progress was swift, and just six weeks after work began the monorail was ready for its first test trains.

The Rhyl Monorail officially opened to the public on 4 July 1980, but the celebrations were short-lived. Later that same afternoon, one of the trains tilted on a curve and became jammed, leaving 40 passengers stranded. Firemen were called to the scene and had to rescue the trapped riders using extension ladders in full view of holidaymakers on the promenade.

Hawes dismissed the incident as little more than teething troubles, remarking: “I’ve built 10 of these systems in the USA, and these things can happen on your first day.” Determined to press ahead, he made swift modifications. Within five days the monorail was running again, with each train fitted with a third wheel for added stability and two extra steel support columns installed along the route.

The Rhyl Monorail received its official opening ceremony on 31 July 1980, with none other than Terry Wogan presiding over the ceremony. Arriving in style by helicopter, he landed on the promenade outside the Westminster Hotel before cutting the ribbon. After its dramatic start, the monorail soon settled into a more reliable routine.

Just a couple of weeks later, a delegation of six Scarborough council officials visited Rhyl to inspect the system, as they were considering a similar line from Spa Bridge to The Corner. Their plans were ultimately abandoned, however, amid concerns that a monorail would “damage the town’s natural beauty.”

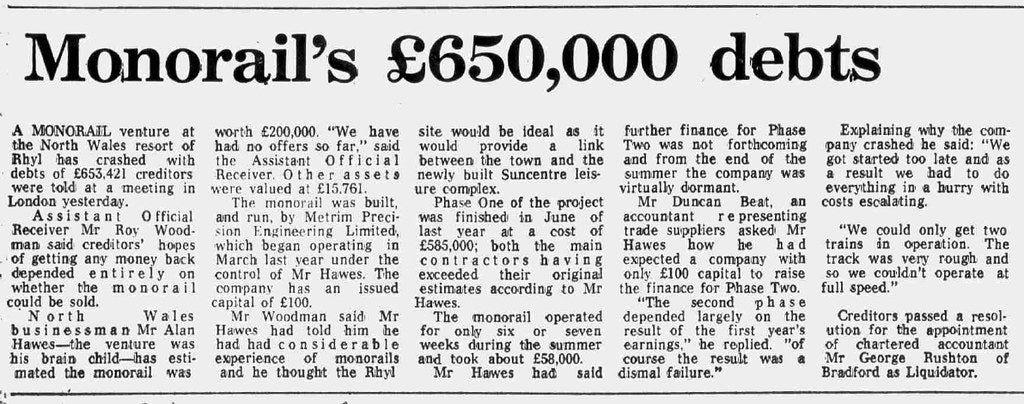

The rest of the 1980 season passed without incident, though revenue was disappointing. Takings were reported at around £58,000—well below expectations.

In December 1980, E&F Engineering of Bridgend announced it was still owed £145,000 for steel track supplied to the Rhyl Monorail. Soon after, a receiving order in bankruptcy was filed against Metrim Precision Engineering Ltd – the company set up by Alan Hawes to run the project. By January 1981, Metrim had entered receivership with debts amounting to £653,000.

The Rhyl Monorail was put up for sale in January 1981, with the council insisting that any new owner would be obliged to complete the second phase of the project, extending the line to the Sun Centre. Later that same month, however, E&F Engineering—still unpaid for its work on the track—was itself forced into liquidation, resulting in the loss of 36 jobs.

Although “several major amusement groups” reportedly showed interest, by April the monorail remained unsold, dashing hopes of a reopening for Easter. The summer season came and went with the system standing idle.

By December, the liquidator accused the council of hindering the sale by insisting on the phase two extension. The council stood firm, arguing that “when they first agreed to the project there was a clear understanding that it would be a transportation system running from West Parade to the Sun Centre.” They pointed out that approval for the first half had only been granted on the basis that the second half would follow the next year. Councillor Hughes added defiantly that the council “would not be bullied into any action which would be against the interests of the borough.”

In January 1982, the council issued an ultimatum to the liquidator, warning that if the Rhyl Monorail was not sold by Easter, they would proceed with its demolition. Alan Hawes had originally deposited a £10,000 bond with the council when the monorail first opened, and this money was earmarked to cover removal costs.

In March, the liquidator’s solicitor made a “personal plea” to the council to reconsider, accusing them of taking “an uncommercial attitude” and arguing that the monorail would “never be sold unless the conditions were less restrictive.”

Just three days before the deadline, a buyer emerged who was willing to operate the monorail for two to three years to test its economic viability. The liquidator explained that “if this proves economically viable, all parties have indicated their willingness to complete the second half.” The council agreed to relax its conditions, granting a two-year license to the potential buyer on the understanding that they would pay a £50,000 bond to cover demolition costs if the venture failed. Ultimately, the deal fell through.

The following month, Alan Hawes returned with an offer to buy back the monorail using funds from American investors, but the council were not interested.

Another summer came and went with the monorail still standing idle. In December 1982, a buyer was finally found: Jack Waite, a businessman from Cheshire who had recently sold his interest in Gwrych Castle. However, Waite was only interested in purchasing the monorail equipment and had no intention of keeping it in Rhyl.

The council gave him until the end of January 1983 to remove the structure and restore the promenade. Waite later applied to convert one of the monorail stations into a restaurant, but the proposal was rejected. By February 1983, the Rhyl Monorail had been completely dismantled, leaving no trace of the ambitious seafront project.

What became of the Rhyl Monorail after its removal remains something of a mystery. In 1986, two of the monorail cars were spotted dumped in a yard in Blaenau Ffestiniog. By 1991, the same two cars had been relocated to Minffordd yard on the Ffestiniog Railway. Some reports suggest that the remaining equipment ended up “under a viaduct in Liverpool,” while two other cars have been seen in the Beeston area, near the marina.

If you have any further information about the monorail’s fate, we would love to hear from you.

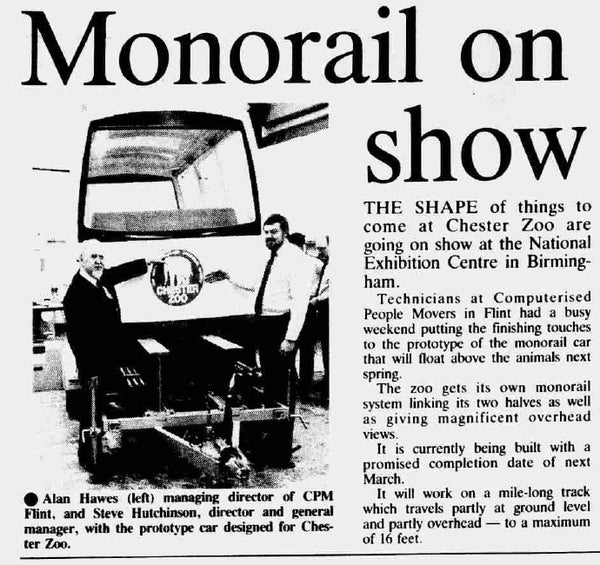

Alan Hawes remained in the Rhyl area, continuing to run AH Design, later renamed Alan Hawes Design. He also established another company nearby in Flint, called Computerised People Movers (CPM), which was involved in constructing a suspended monorail at Blackpool Pleasure Beach in 1990 for the Wonderful World ride, as well as another monorail at Chester Zoo in 1991.

Reflecting on the Rhyl Monorail in 1989, Alan Hawes remarked: “It was a great success in many ways. It was built in little more than 60 days, which was a miracle in itself, and in just over a month it took £60,000.”

We’d love to hear your memories and stories of the monorail. Please feel free to leave a comment below.

Alan Hawes was my uncle, I remember the monorail in Wales, he lost a lot of money, including family money, he thereafter lost contact with most of his family, he never repeated the success he had in America in his younger years.