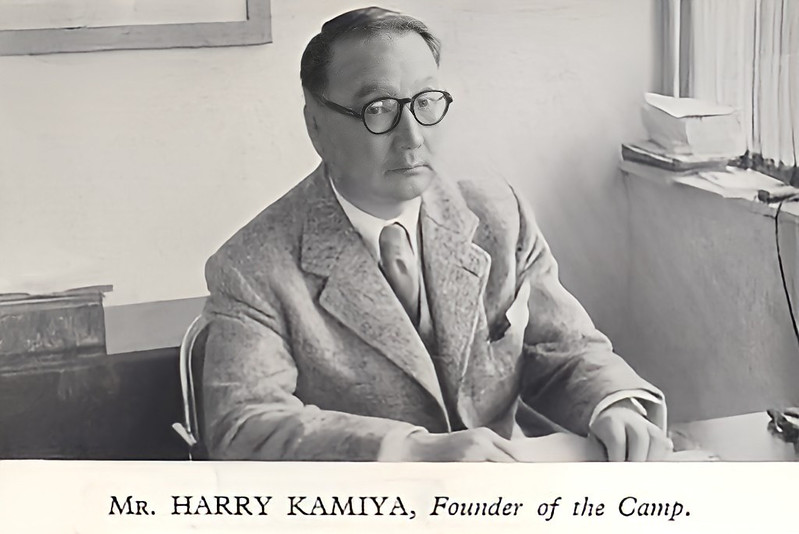

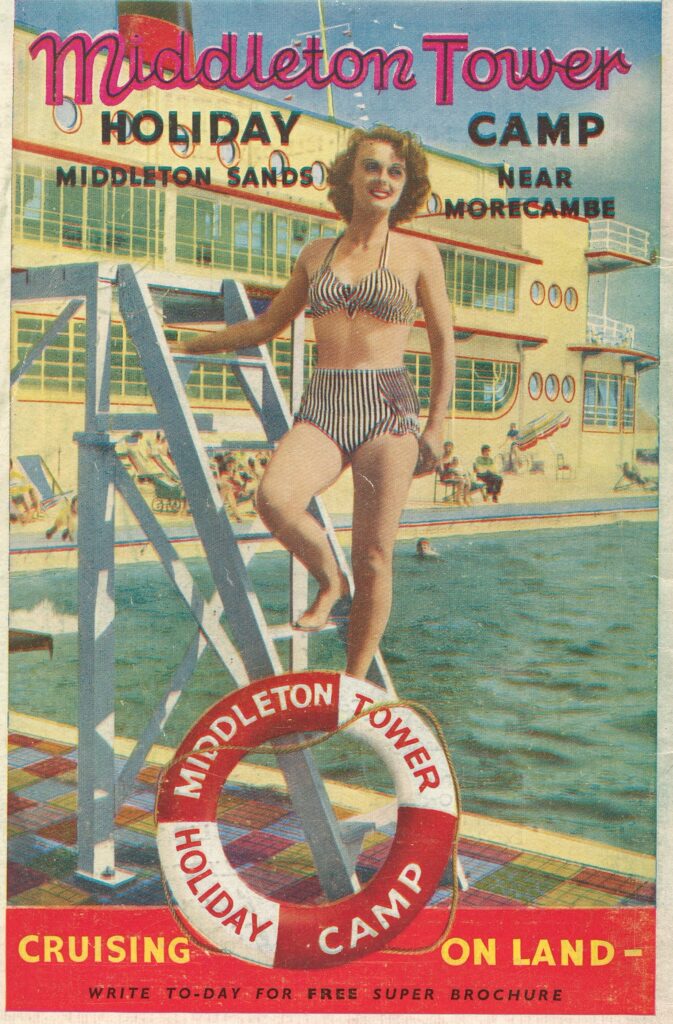

Located near Heysham, around five miles south of Morecambe, Middleton Tower Holiday Camp opened its gates in June 1939. The 65-acre full-board resort was the brainchild of Shohimon “Harry” Kamiya, a Japanese businessman and amusement concessionaire from Blackpool. Built at a cost of £52,000, the camp was officially inaugurated by Lady Bridget Poulett, who ceremonially sliced into a 200-pound cake shaped like the site’s 17th-century towers.

At launch, Middleton Tower offered 600 chalets with weekly rates of £3 per person. Among its early investors and directors was Leslie Salts, who would later become known for acquiring Gwrych Castle in North Wales.

The Story of Middleton Tower’s Ocean Liner Relics

Whenever the history of Middleton Tower is told, the legend of the ocean liner relics is never far behind. The story goes that the camp’s grand “Berengaria” building incorporated fittings from the Cunard liner of the same name, salvaged before the vessel was scrapped. Pontins themselves leaned on this tale in their brochures throughout the 1970s and 1980s, and when the camp finally closed, there was even talk of trying to preserve these valuable relics.

And yes – the story is true. The Berengaria building did indeed once contain pieces from the famous ship. The twist, however, is that they were mostly all gone by the time Pontins acquired the camp.

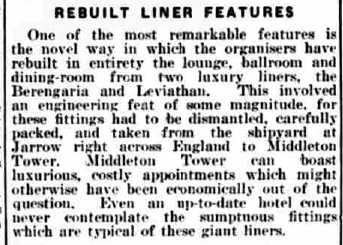

The tale begins in the late 1930s, during construction of Middleton Tower. Teams of workers were dispatched to Jarrow to strip fittings from the RMS Berengaria and the RMS Leviathan. Both ships had begun life in Germany, seized by the Allies at the end of the First World War, and by 1939 both lay idle awaiting the breaker’s torch.

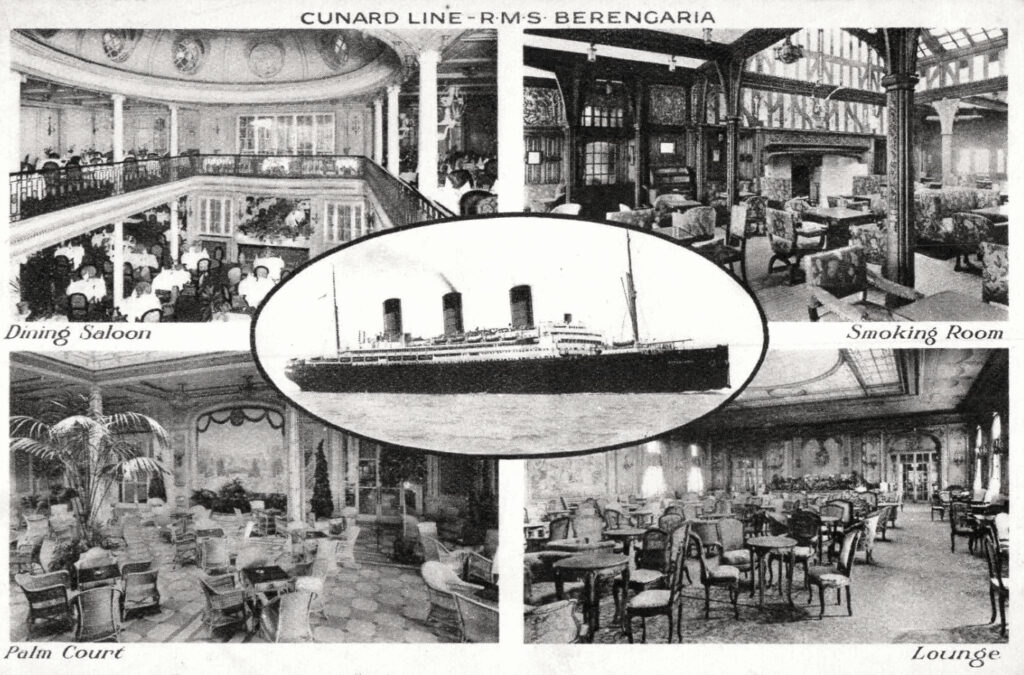

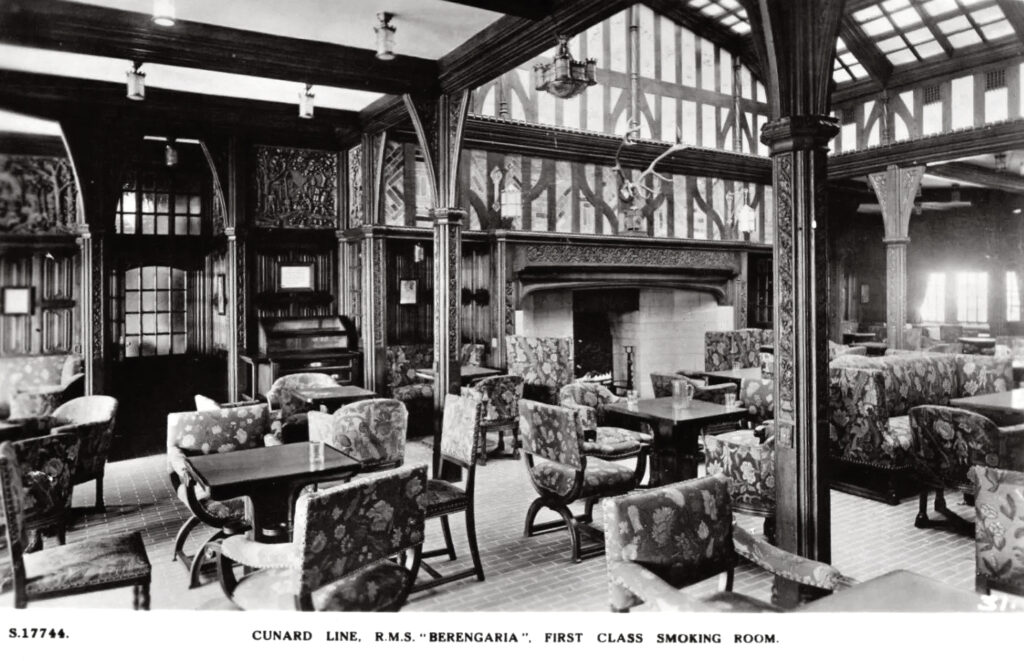

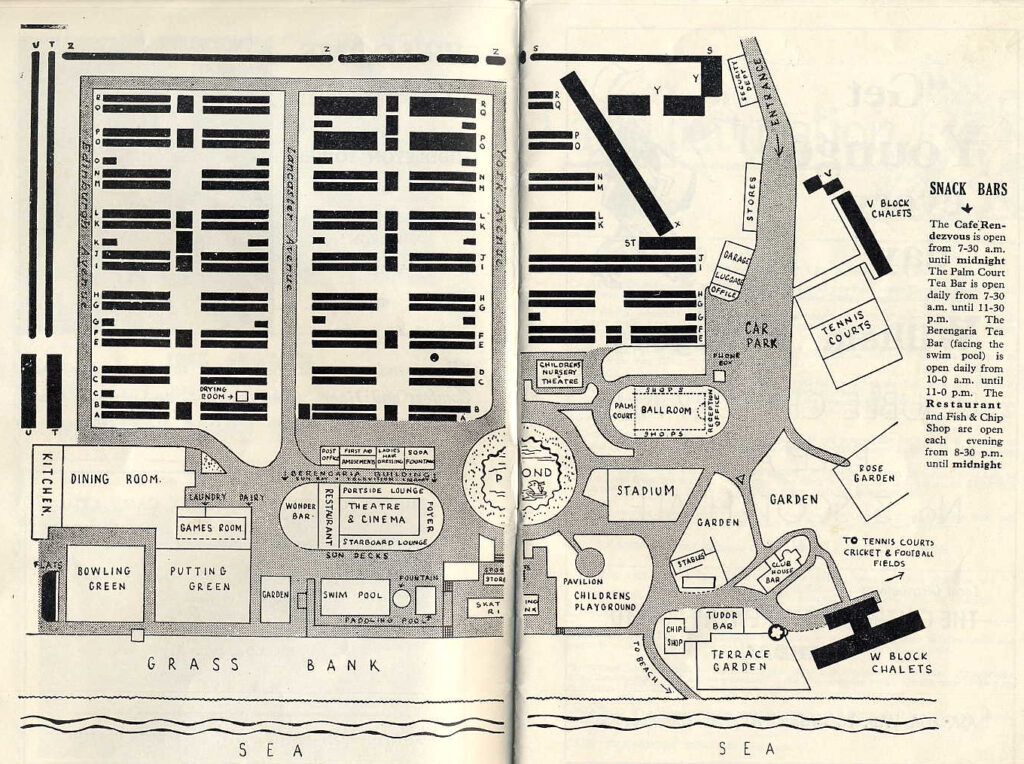

At Middleton, these fittings found a second life. The main building – housing the camp’s enormous communal dining hall – was furnished with the Berengaria’s cocktail bar and smoking room, while the dining space itself displayed more relics, including four vast 15ft by 12ft paintings taken from the liner.

The camp’s other great structure was the ballroom, and here the Leviathan’s treasures were installed. In fact, the entire ballroom of the ship was reconstructed “right to the last wall panel and wall light.” The adjoining Palm Court, too, was transplanted wholesale, giving holidaymakers the rare experience of dancing and dining amid the décor of two once-great ocean liners.

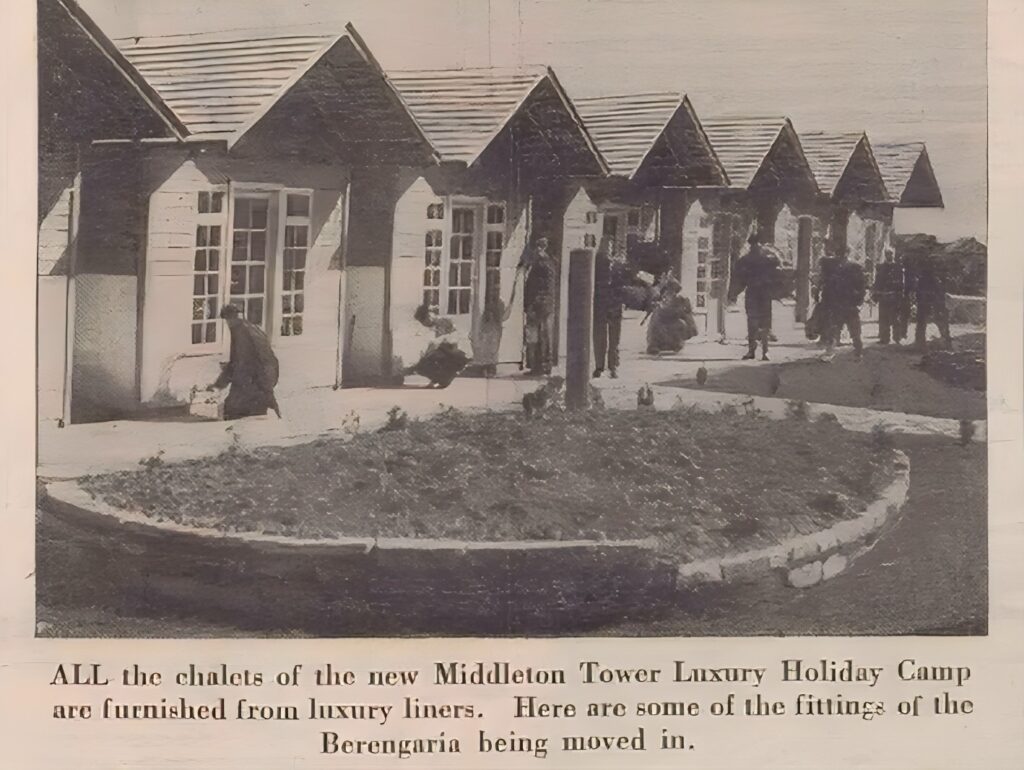

So many fittings were salvaged that relics from the liners found their way into other buildings across the camp. Workmen were even dispatched with smaller items—knick-knacks, light fittings, ornaments, and bits of trim—which were placed in every chalet on the site. Needless to say, they didn’t stay there for long. Guests quickly pocketed them as souvenirs, and before long, most had vanished. Whenever a small relic from either ship appears for sale today, there’s every chance it once adorned a humble chalet at Middleton Tower.

The fate of the main ship fittings, however, was a tragic one. In 1948 the Berengaria building was completely destroyed in a ferocious blaze that gutted the structure in just half an hour, consuming every last relic inside.

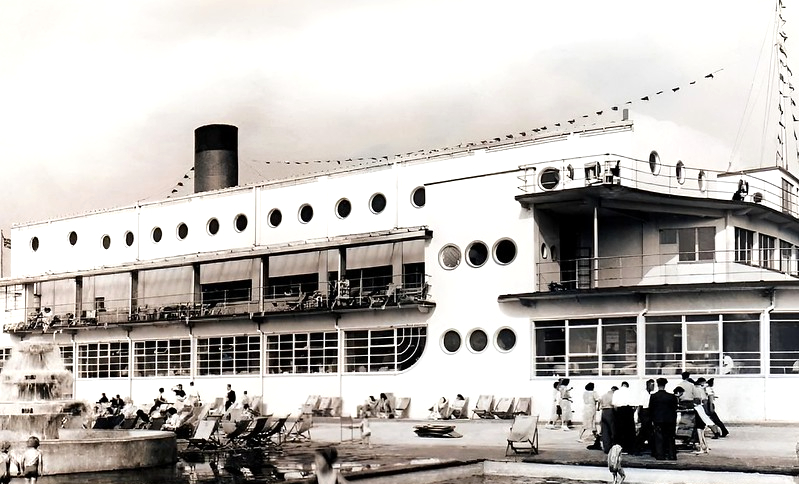

The following year it rose again, rebuilt with “fire-proof materials” and formally reopened by the Bishop of Lancaster. Its new exterior styled to resemble a real ocean liner, complete with portholes, funnel, and promenade decks, while inside it now housed a 2,000-seat theatre, with the dining hall moved to a new building nearby.

Disaster struck again in 1955 when another fire tore through the building, collapsing the roof. Although the shell survived, the interior had to be rebuilt once more.

The Leviathan building fared no better. In January 1959 it too was reduced to ashes in a devastating fire, destroying the ballroom and Palm Court interiors salvaged two decades earlier. It was rebuilt at a cost of £100,000 and reopened in June that year by comedian Al Read.

By the time Pontins purchased Middleton Tower in 1960, all of the original relics inside the Berengaria Building and ballroom had long since disappeared. A few, however, survived in other corners of the camp. In the mid-1980s, some of these pieces found a new home when they were sold to the Scale Hall Country Club in Lancaster, which itself later closed and sat abandoned.

The post-war years

The site was requisitioned for wartime use just 6 weeks after opening, but it reopened again in June 1946. John Lennon’s dad spent the 1950 season working here as a dishwasher. Harry Kamiya died in 1951 and operation of the camp was taken over by his wife Nellie and daughter Jean.

Pontins Takes Over

In September 1960, the Berengaria played host to the 14th annual Middleton Beauty Contest, with none other than George Formby and television presenter Bill Grundy among the judging panel. Just a month later, the site was sold to Pontins in a deal worth £540,000 – a major milestone that marked the company’s first move “up north.” The following year, Pontins strengthened its northern presence with the purchase of its Blackpool camp.

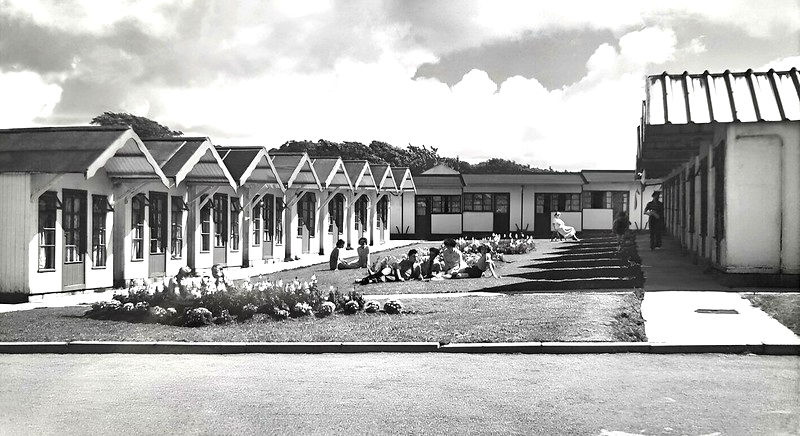

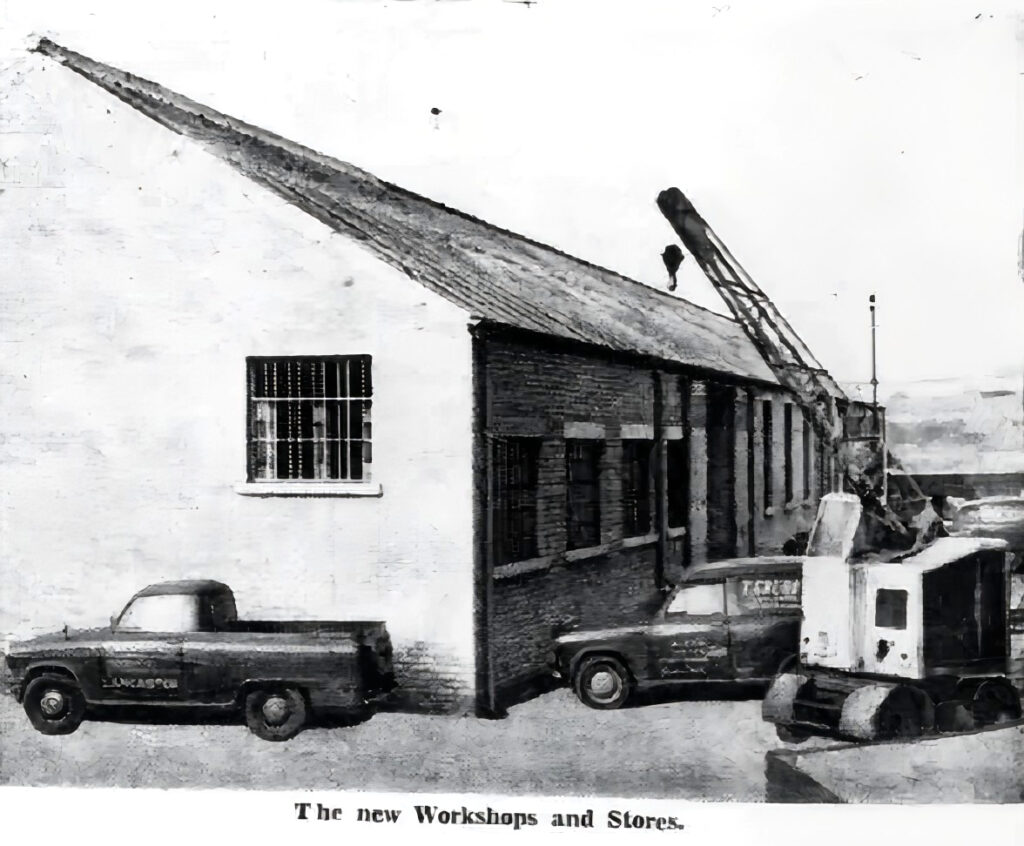

The chalets at Middleton Tower were built during a period when building materials were rationed in anticipation of war, and many were said to have been of a temporary nature. Fred Pontin later remarked that they were made from “old packing cases.” Wasting little time, Pontins began expanding and improving the camp on a grand scale. The construction engineer was Bill Armistead who had also overseen the rebuilding at the Blackpool and Wick Ferry camps. The site retained its full-board status, and within the first three years the company invested £300,000 to demolish 400 of the old chalets and replace them with 250 modern apartments – each reportedly costing £240.

Half of the budget went towards constructing a vast new dining hall, reputedly the largest in Europe at the time. Designed to seat 3,000 guests in a single sitting and staffed by 130 waitresses, it featured a state-of-the-art kitchen equipped with rotary ovens capable of roasting 400 chickens at once. Beneath the dining area, a smaller ballroom and bar were also added. The outdoor swimming pool was upgraded too, enclosed within a new heated building for all-weather use.

The former dining hall, originally built in 1949 following the first Berengaria fire, was repurposed as an infants’ centre- serving an average of 150 babies each week. Part of it was also converted into a games room. In a twist of irony, this building itself was destroyed by fire in 1976, though it was subsequently rebuilt.

As a full-board camp, Middleton Tower’s chalets were built in a motel style – essentially just a bedroom and bathroom, with no lounge or kitchen facilities. Most were arranged in single-storey blocks, though a few two-storey blocks were added along the northern edge to help shield views of the nearby ICI factory.

The camp became the largest in the Pontins empire and Eric Bennett, formerly in charge at Butlins Filey, was recruited to manage it. He later went on to oversee the Pontins Blackpool camp as well, giving him the distinction of having managed three of the largest holiday camps in the country before retiring in 1985.

In 1975, the theatre inside the Berengaria Building was converted into a nightclub, with the old tiered seating removed and replaced by tables and chairs—an alteration said to have been made to boost alcohol sales. The following year, the venue enjoyed a moment in the national spotlight when it hosted the Miss Great Britain grand finale, broadcast live on television. The competition was won by Dinah May, who received a £3,000 cash prize, a mink jacket, a watch, and a continental holiday.

In August 1977 over 300 guests were taken ill by a mystery illness. After conducting stringent tests the environmental health office said they were 99.9% certain it was caused by an airborne virus and not food poisoning.

Bradley Walsh spent 3 months working here as a bluecoat in 1982.

From the mid-1980s onward, Middleton Tower entered a period of decline, both in visitor numbers and in its general appearance. The boom years were over, and the camp was struggling to stay afloat. Maintenance and repairs were scaled back, and the once-bustling holiday atmosphere began to fade. This difficult period was also marked by tragedy, including the drowning of an eight-year-old boy in the swimming pool in 1987, and a chalet fire in 1991 that claimed the life of 19-year-old employee Billy Howard.

The camp didn’t even appear in the 1994 Pontins summer brochure—a telling sign of its uncertain future. That September, it experienced a memorable power cut just as comedian Tony Jo stepped onto the stage. With no lights and a dead microphone, he carried on his act in complete darkness for 90 minutes, to the delight of the audience. One camper later recalled, “It was very reminiscent of the war years. There was a right good atmosphere.” Sadly, just a month later, Middleton Tower closed its doors for good.

Post-Closure and Redevelopment Efforts

After the camp closed, the site saw a series of unusual and ultimately unsuccessful ventures. In 1995, plans were announced to film a movie at the camp titled Raving Beauties, starring Steve Coogan as a sexist holiday camp owner. The project was later scrapped and never came to fruition.

In early 1996, a company called Breakpoint secured a 12-month lease on the site, announcing plans to refurbish and reopen it as a holiday camp. They also intended to host monthly music concerts – a prospect that drew strong opposition from local residents. The Parish Council also added their voice, stating that the camp “is in a virtually derelict condition and is in no fit state to entertain visitors.”

The first event under Breakpoint’s management took place over Easter 1996: a rave dance festival that attracted over 3,000 attendees. After the festival, the company vanished, leaving around £60,000 in unpaid debts to local businesses. The lease was subsequently terminated.

In December 1996, plans were announced to convert the former holiday camp into a temporary Category C prison. A Lancaster City Council spokesman explained, “No new buildings are planned, just a 15-foot fence.” The proposal drew plenty of attention—and a touch of humour. A Daily Express columnist quipped, “Good morning campers! Today’s bonny baby competition has been cancelled, and there will be no karaoke or ballroom dancing. We can, however, offer mail-bag sewing in the workshops, and if you have been a little too Hi-de-Hi lately, there is drug therapy in the hospital wing.”

Despite strong local opposition, the scheme was approved following a public inquiry, but the plan was later abandoned when officials opted instead to build a new permanent prison at Maghull, Merseyside.

In September 1999, the site was sold to a development firm, CJ Homes, which unveiled ambitious plans to transform Middleton Tower into the UK’s largest retirement community. The company promised a £50 million investment, and outline planning permission was granted for 650 homes. However, progress soon stalled, and by 2003 the land was back on the market with an asking price of £12 million.

Nothing further happened for several years, and the once-bustling holiday camp lay derelict and abandoned. Demolition finally began in 2005, sweeping away the last remnants of the old buildings. Construction on the new housing project followed, but the venture collapsed into bankruptcy after only 55 homes had been completed. Another 18 years passed before new planning permission was finally granted in 2023 for the construction of an additional 50 houses.

Middleton Tower today

The only surviving traces of the holiday camp era are the Grade II listed 17th-century farmhouse and its adjoining barn. During the camp years, the farmhouse operated as the popular pub Ye Olde Farm House and was reputedly haunted. The barn initially housed the ‘Tudor Bar,’ later transformed into a nightclub, and eventually a staff-only bar.

Today, both buildings have been converted into a large five-bedroom holiday home, complete with an indoor pool, games room, and sauna, and available as an airbnb rental. At the time of writing, the old circular fish pond that once stood in front of the Berengaria building also still remains.

We’ve also covered the history of several other Pontin camps which can be found in our A-Z blog index.

We’d love to hear your stories and memories of Middleton Tower. Please feel free to leave a comment below