In the early 1970s, London’s tourist scene was a fairly tame affair. Visitors were shepherded through museums, stately homes and historic sites where the gory parts of history were politely glossed over. It was all very proper – and, to many younger visitors, terribly dull. But in 1972, one woman decided to change that.

Annabel Geddes was a 34-year-old divorced mother of three who freely admitted to being “a middle-class housewife, bored and frustrated to screaming point.” The idea that would change her life – and add a new dimension to London tourism – came almost by accident.

One afternoon she took her children to the Tower of London, expecting them to be fascinated by tales of beheadings and intrigue. Instead, they were distinctly underwhelmed. “What a boring old place,” they complained on the drive home. “There was no blood, no rats… nothing.” Half-jokingly, one of them suggested, “Why don’t we open a torture chamber?”

“I thought it was a jolly good idea,” Annabel later recalled – and, remarkably, she decided to do exactly that. Geddes had no experience of history or horror, so she started from scratch: reading, researching, and asking endless questions. Her aim was to build the only medieval exhibition of terror and torture of its kind in the world – something atmospheric, authentic, and just a little shocking.

British Rail eventually helped her locate a suitably grim home: a 200-year-old former wine warehouse located in brick arches beneath London Bridge station on Tooley Street. The 27,000-square-foot space was damp, musty smelling and echoing, with water dripping from the brickwork. The commuter trains running above only added to the experience by providing a ghostly rumbling sound. It was, as she put it, “ideal for a torture museum.” Even the site’s history seemed to play along – Tooley Street had once housed a real private torture chamber and a plague burial pit, and during the Blitz a German bomb killed 63 people on nearby Stanier Street.

Geddes took out a 21-year lease at an initial rent of £7,700 a year and began raising the £50,000 she needed to bring her gruesome vision to life. Hugh Foster, a chartered accountant, joined her to manage the finances, while Dr Alan Borg of the Tower of London came on board as a historical adviser. Determined that every instrument and costume should be authentic, she enlisted craftsman Peter Hewitt to build the exhibits to her exacting specifications.

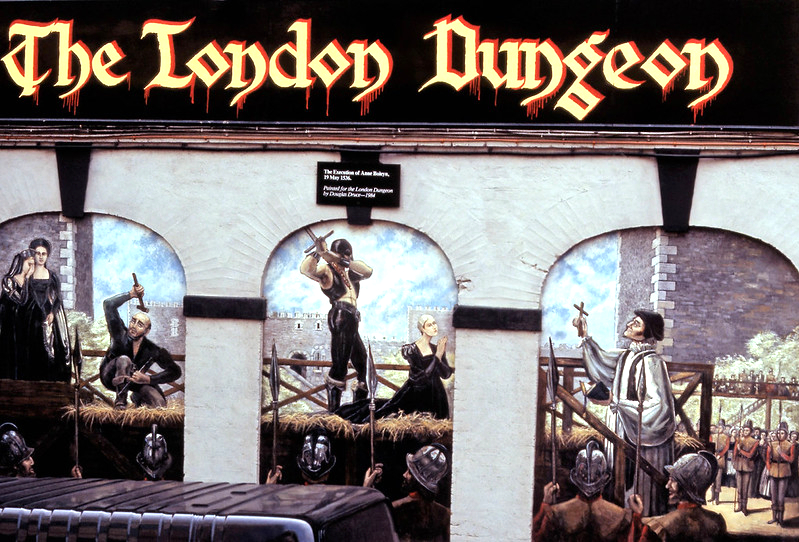

By the summer of 1975, the work was complete. The London Dungeon opened that August, proudly billed as an “exhibition of medieval degradation, damnation and death.” Admission was 80p for adults and 30p for children.

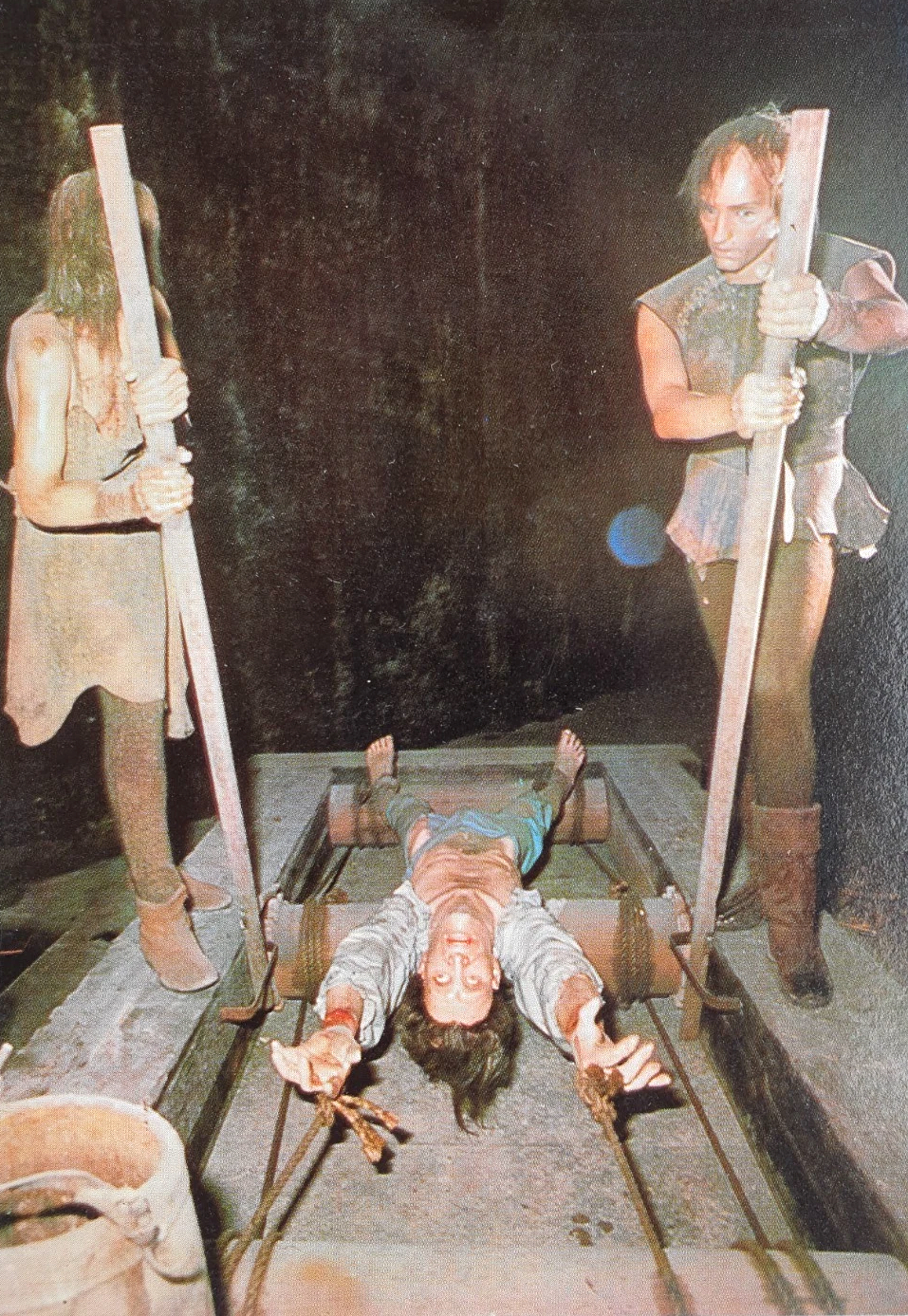

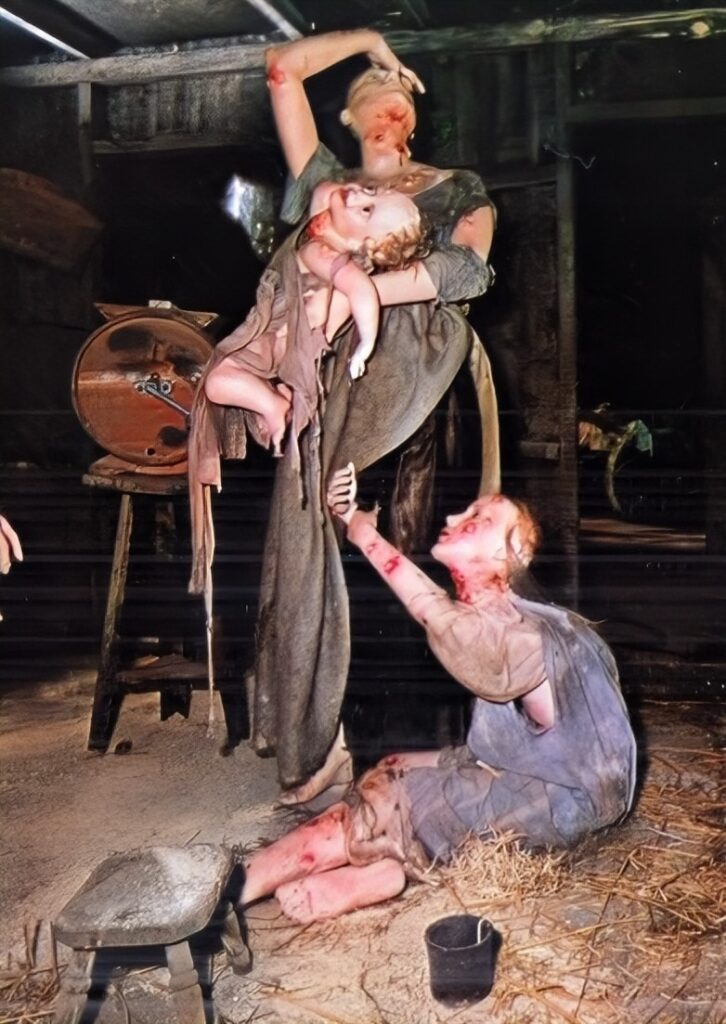

Inside, visitors were greeted with a series of waxworks and grisly tableaus – torture, burnings at the stake, human sacrifice, beheadings, and hangings. Dismembered heads leered from spikes while ghostly sounds echoed from the shadows. In one scene, St. George hung in crucifixion; in another, Boadicea plunged her spear into a Roman soldier’s throat. Victims of the Reformation burned at the stake amid flickering candlelight, dim lighting and musty smells.

The final chamber – a grim recreation of the Tower of London’s torture room – carried a warning sign:

“Not recommended for nervous or squeamish visitors. Under no circumstances can the management accept responsibility for subsequent nightmares.”

It was a fitting disclaimer for an attraction that would go on to terrify – and delight – millions.

One notable exhibit stood out amid all the torture devices and wax effigies – a small, blood-stained handkerchief said to have been carried by King Charles I at his execution. Geddes had bought it at a Christie’s auction in January 1975 for £367, proudly displaying it in a glass case near the entrance. It quickly became one of the Dungeon’s star curiosities, lending a touch of real history to an attraction otherwise filled with recreated horror. But in 1978, just three years after the Dungeon opened, the relic vanished – stolen straight from its case.

The London Dungeon captured a new mood in 1970s Britain – one that mixed dark humour with an appetite for the macabre. Part history lesson, part haunted house, it tapped into the same fascination with horror that filled cinema screens with Hammer films and Gothic thrillers. What began as the idea of one “bored housewife” soon became an instant success, and a well-loved London institution. Geddes later commented “I may drive around in a Jaguar XJS but I still have to work like hell 7 days a week:”

In 1980, British Rail delivered a devastating blow to the dungeon’s finances when it increased the annual rent from £7,700 to £75,000 – almost a tenfold rise overnight.

Not all of the Dungeon’s horrors were confined to the exhibits. In 1981, the Greater London Council’s social club hired the venue for its annual staff party – a decision that proved rather costly. By the end of the riotous evening, several displays had been damaged, and the Dungeon management promptly sent the GLC a repair bill for £2,000, along with a lifetime ban from the premises. The club’s chairman seemed somewhat taken aback by the scale of the damage. “I did notice that a couple of heads had been knocked off,” he admitted, “but I thought they could have been glued back on. I had a letter saying there’d been some damage, but I didn’t think it would be £2,000. I thought it was just a minor mishap.”

During its early years, the Dungeon also introduced a tongue-in-cheek annual tradition known as the Pillory Award – a public poll asking visitors to vote for the person they’d most like to see pelted with rubbish in the stocks. It was all in good humour, of course, and the winners reflected the quirks of 1970s British popular opinion. Among those “honoured” were novelist Barbara Cartland and entertainer Des O’Connor.

The exhibits later became more interactive, and the introduction of live actors added a new dimension. By 1983, the London Dungeon had become a runaway success. What began as a quirky experiment in a damp railway arch was now pulling in annual profits of around £200,000 on a turnover of £600,000 – impressive figures for what was essentially a museum of misery. That December, the attraction was sold to Kunick Leisure for a cool £1 million.

Kunick, headed by Sir Fred Pontin (of Pontins Holiday Camp fame) and Scarborough businessman Don Robinson, was an unusual mix of interests – running everything from fruit machines to nursing homes. Annabel Geddes agreed to stay on for a while as managing director under the new ownership, ensuring that the Dungeon’s trademark mix of historical horror and dark humour remained intact.

Kunick wasted little time expanding the concept. In July 1986, a second Dungeon attraction opened in York, taking the same formula of historical horror and local legend north. By then, the original London Dungeon was drawing huge crowds, with admission priced at £3.50 for adults and £2 for children – roughly on par with Madame Tussauds, which says much about how firmly it had cemented itself in the capital’s tourist circuit.

The company’s most ambitious move came in 1990, when the Kunick Group spent an estimated £2 million opening a continental counterpart in Paris. The new attraction, named Les Martyrs de Paris, was located beneath the Forum des Halles near the Porte du Louvre, and followed much the same grisly blueprint as its British cousins. However, the French authorities were less enthusiastic about such macabre entertainment. Local officials promptly banned all children under twelve from entering, which hardly helped attendance figures. Despite attempts to adapt the formula for Parisian tastes, Les Martyrs de Paris never really took off – and by 1993, the attraction quietly closed its doors for good.

By the late 1980s, the London Dungeon had become a firm fixture on the tourist trail – even attracting a touch of royal curiosity. In 1989, Princess Diana paid a visit with young Princes William and Harry, and two years later the Duchess of York, Sarah Ferguson, came with her daughters, Beatrice and Eugenie.

The Dungeon’s appeal showed no sign of waning. In 1990, it welcomed 580,000 visitors, a record year that confirmed its status as one of London’s top-paying attractions.

In March 1992, Kunick decided to capitalise on the growing success of its attractions, selling both the London and York Dungeons to Vardon Leisure for £5.6 million. At the time of the sale, the two sites were together generating an annual turnover of £2.2 million, with profits of £1.26 million. Later that same year, Vardon expanded further by purchasing the Sea Life company and its nine aquariums for £9.9 million, laying the groundwork for what would soon become a major player in the UK leisure industry.

In 1997, a major new feature opened – a £3.5 million water ride grandly titled Judgement Day: Sentenced to Death. The dark boat ride carried visitors on a one-way journey to their execution, culminating in a backward drop down a slope. Unfortunately, the grand launch didn’t quite go to plan. At the official opening, the brand-new ride promptly broke down – meaning that not a single invited guest actually got to experience it. Still, once the gremlins were fixed, Judgement Day became one of the Dungeon’s biggest draws.

In 2004, the ride was reworked and relaunched as Traitor! – Boat Ride to Hell. Much of the original opening sequence was scrapped, and the ride’s ambitious turntable lift system was replaced with a more conventional lift hill. Even so, it remained one of the most popular – and unnerving – parts of the London Dungeon experience

By the 2010s, the Dungeon had outgrown its original home and was now struggling to cope with the crowds. There was no indoor queuing area, so visitors often found themselves snaking down the pavement in all weathers – a miserable experience on a cold, wet London afternoon.

A new site was eventually found inside the old County Hall building on the South Bank, just a stone’s throw from the London Eye. It was a more central location for tourists and, crucially, offered far more space. The original Dungeon closed its doors in January 2013, and the new version opened barely two months later. Some of the old props made the move across the river, but many were replaced by freshly built sets and effects. Annabel Geddes died later that year aged 75.

The new South Bank location offered a slightly softer experience, with less gore and less emphasis on torture. Long-time visitors lamented the loss of the original Dungeon’s atmosphere, arguing that Tooley Street actually felt like a real dungeon – dark, damp, and oppressive. Others, however, welcomed the change, praising the County Hall version for being bigger, more polished, and filled with theatrical flourishes.

Vardon Leisure would later evolve into Merlin Entertainments, which has since become one of the dominant forces in the UK tourism industry. Building on the success of the original attraction, the company went on to open four more Dungeon experiences across Britain – in Blackpool, Edinburgh, Warwick Castle, and Alton Towers – along with five international versions in Amsterdam, Berlin, Hamburg, Shanghai, and San Francisco. Not all of these have stood the test of time, but together they helped turn the Dungeon brand into a global phenomenon.

The old Tooley Street premises stood empty for the next twelve years, their dark passageways and crumbling brickwork slowly gathering dust. But in 2025, the building found a new lease of life when it was taken over by Wetherspoons and transformed into a pub named The Sun Wharf. Before opening, the company staged a rather fitting publicity event – a “cleansing séance” led by a local medium, who claimed to have guided any lingering spirits across the river to the new Dungeon on the South Bank.

The restoration was extensive. The original exposed brickwork was carefully cleaned and preserved, and the entire building was brought back to life at a cost of £2.75 million – a sympathetic revival for a structure that had once terrified generations of visitors.

We’d love to hear your stories and memories of the dungeon. Please feel free to leave a comment below.