In 1947, the British coal industry was nationalised, and the following year the East Midlands division reported a £7.8 million profit, making it the most successful coalfield in the country. To reward his workforce, Sir Hubert Houldsworth, chairman of East Midlands, announced a holiday charter for the 97,000 miners across Derbyshire, Nottinghamshire, and Leicestershire. Plans were drawn up for four holiday camps. “No men work harder than the East Midlands miners,” Sir Hubert declared. “Their output per man shift is nearly 50% higher than the rest of Britain’s miners. Men who sweat and toil like them have the right to expect good holidays.”

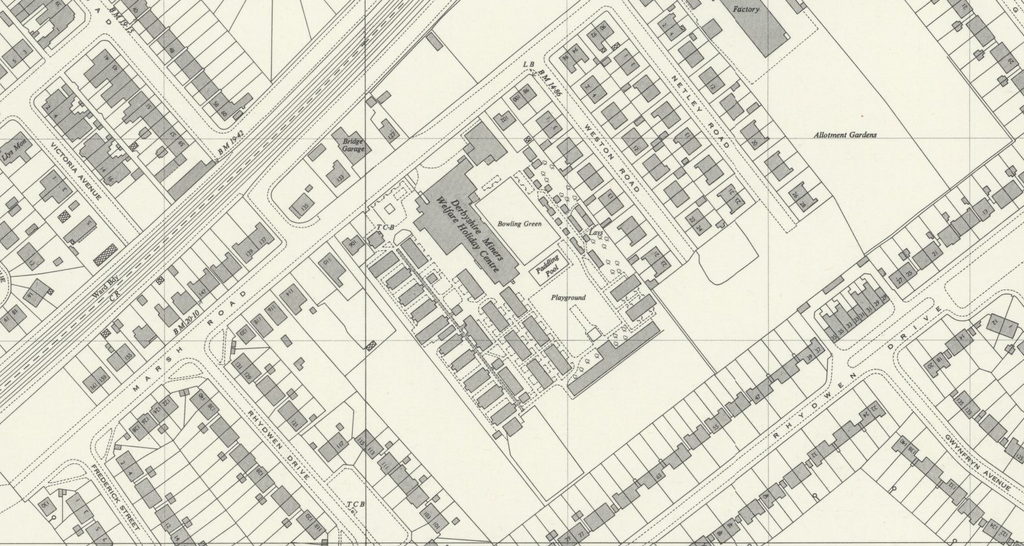

The first camp opened in Rhyl in July 1948. Covering five acres, the site had previously belonged to Bolsover Colliery and had been used as a camping ground for youth organisations. Sir Hubert took inspiration from the Miners Welfare Commission’s Skegness camp. The cost was deliberately kept low—just £3 per adult per week, around half the price of comparable camps and hotels—making a proper seaside holiday accessible to working miners and their families.

The British Federation of Hotels and Boarding Houses strongly objected to the government entering the holiday camp business. “The federation has every sympathy with the miner,” they said, “but it does not believe he is entitled to subsidised holidays.” By an overwhelming majority, they voted to oppose the establishment of any further government-run holiday camps.

Local hoteliers in Rhyl were similarly displeased. The Rhyl Hoteliers Association described themselves as “alarmed” by the news, noting that “Rhyl landladies cannot possibly compete with the Coal Board at their prices.” In response, a spokesman for the National Coal Board clarified the purpose of the scheme: “The emphasis is on rest and homely holidays. Bathing pools, cinemas, and entertainments are not part of the proposed amenities.” He stressed that it was not a conventional holiday camp, adding, “We are avoiding the term ‘camp’. Ours is a holiday centre with no regimentation or interference,” and emphasised that the primary attractions would be “good food and good cooking.”

The following year, the British Federation of Hotels formally wrote to the National Coal Board (NCB), urging them to either abandon the Derbyshire Miners Holiday Camp or at least charge commercial rates. “Boarding house keepers are going to suffer considerably,” they warned, “as they rely to a large extent on visitors from the Midlands mining area.”

Later that same year, management of the camp was transferred to a joint committee made up of the NCB and the Derbyshire Miners Association. The site was now to be run along the same lines as the larger Skegness camp, catering exclusively to Derbyshire miners. A key factor in this decision was that Derbyshire was the only county to stagger miners’ summer holidays over a sixteen-week period, ensuring a steady flow of visitors. With this model in place, the NCB abandoned plans to open any further camps.

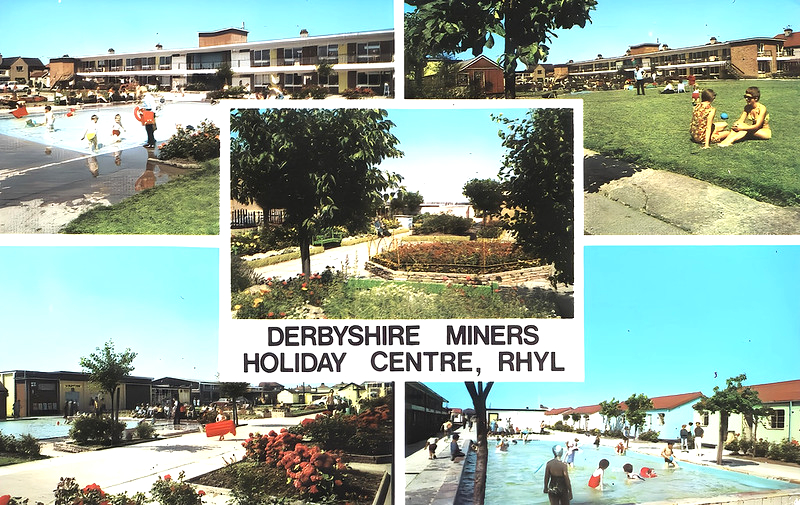

Originally, the camp had a capacity of 250 guests, but in 1951 a £17,000 investment in new chalets expanded this to 400. Four years later, another £6,000 was spent on adding a cocktail bar and sun lounge, further enhancing the facilities and comfort for the miners and their families.

The camp remained popular throughout the 1960s and a new theatre, ballroom and outdoor swimming pool were built. Some of the chalets were fitted with central heating and the camp started opening during the winter months.

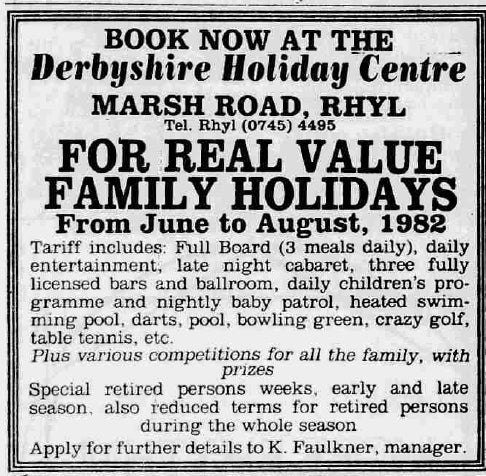

Starting in the late 1970s, the camp began to experience a downturn in business, largely due to the decline of the mining industry. In May 1980, it was sold to Western Motor Holdings for £250,000 and rebranded as The Derbyshire Holiday Centre.

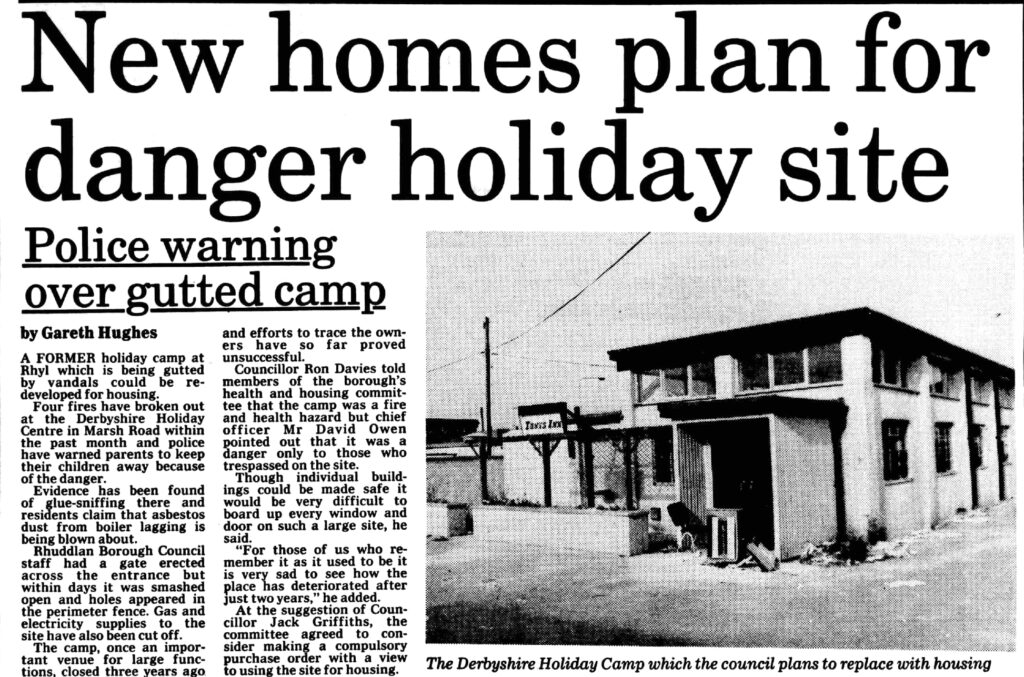

In December 1983, the camp changed hands again, this time to Gem Leisure, whose new owners announced plans for a £6 million investment to modernize and expand the site. Work began immediately, but within a year the venture collapsed into liquidation. The camp closed in December 1984, resulting in the loss of 12 permanent jobs. It was subsequently put up for sale with an asking price of £200,000.

No buyer was found, and the camp remained abandoned. Over the following years it suffered repeated vandalism, incursions by squatters, and numerous arson attacks. The fires became so frequent that the local council eventually gave the fire brigade a key to the site for immediate access.

In 1989 the derelict site was sold for housing development, and the remaining structures were demolished the following year. In December 1992, a new residential complex of 94 homes was officially opened by David Hunt, Secretary of State for Wales.

Where was it located exactly? Search out Chatsworth Rd, Haddon Close and Thornton Close in Rhyl.

We’d love to hear your memories and stories of the camp. Please feel free to leave a comment below.