Luton Stadium opened in 1931 as a greyhound racing track. Over the years it became a popular but modest operation, lacking many of the modern facilities found at larger or more prestigious tracks.

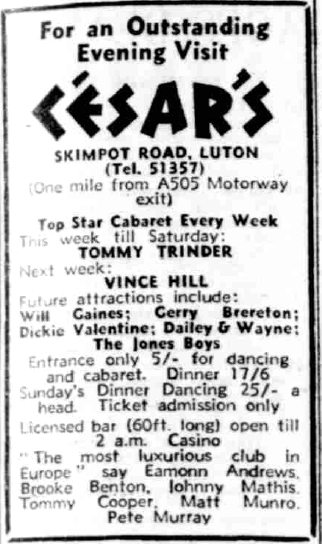

Everything changed in October 1966 with the arrival of a bold new development beside the stadium: a sprawling entertainment complex launched under the lavish name of Cesar’s Palace. Marketed as a concept unlike anything else in Britain, it brought together a mix of attractions under one roof. Alongside a purpose-built cabaret room – complete with a rising dance floor – patrons could enjoy a casino, restaurant, bingo hall, 14-lane bowling alley and a disco. The project was developed by Arbiter and Weston and was officially opened by comedian Tommy Cooper.

While cabaret clubs in the North of England had been thriving – once described as “flourishing like grapes in Italy” – Cesar’s Palace represented the first serious attempt to introduce the same large-scale formula to the South. Blending a hint of West End glamour with the more accessible atmosphere of the Northern club circuit, the venue quickly became a huge local talking point.

The opening night was staged with full theatrical flair. Doormen were outfitted as Roman soldiers, the nearby M1 motorway was temporarily rechristened “Chariot Way,” and guests were attended to by a team of “voluptuous maidens.” During the celebrations, Eamonn Andrews reportedly invited Tommy Cooper for a pre-show drink, to which Cooper replied, “Oh no, I never drink before a show – I might get the tricks right.”

Cesar’s Palace featured its own resident troupe of six dancers, choreographed and led by Sandra Blair. Their performances, staging and costumes were widely praised, and described at the time as being of a standard “seldom before seen in provincial nightlife.”

The guest list for the opening was suitably star-studded, including the Earl of Arran, American singer Brook Benton, Peter Murray, Don Black, Vic Lewis, Matt Monro, Elaine Delmar and Eamonn Andrews himself, who had a financial stake in the operation being a director of Arbiter and Weston.

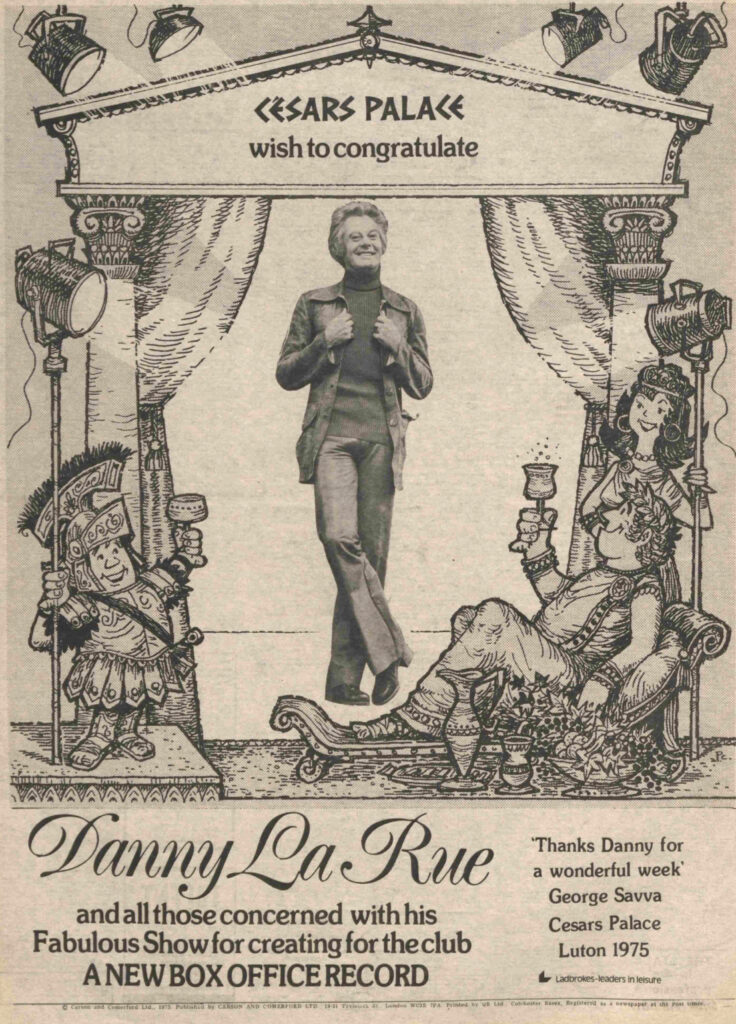

Originally licensed until 2 a.m. and open seven nights a week, Cesar’s Palace wasted no time attracting high-profile bookings from both established British entertainers and international stars including Shirley Bassey, Mike and Bernie Winters, Lulu, Frankie Howerd, Frankie Vaughan, the Barron Knights and Dickie Henderson. Within just a few months, it had earned a reputation as one of the most glamorous and talked-about nightspots in the country. One of the most talked-about moments came in 1969 when, during a performance by Johnnie Ray, Judy Garland unexpectedly joined him on stage – a brief but unforgettable appearance that added to the club’s growing legend. Much of this success was credited to its dynamic manager, George Savva, who would later become a legendary figure in the industry, and widely known as “Mr Showbiz.”

It was known as a “chicken-in-a-basket” club, where the ticket price included both a meal and the evening’s entertainment. The menu was usually fixed – scampi and chips and chicken and chips were both favourites. Once the plates were cleared, the lights dimmed and the evening entertainment began, often with a support act. Tickets could also be purchased for admission only. As with most venues of this type, alcohol sales were a crucial part of the business model – and often made the difference between making a loss or earning a profit.

In 1970, the government published a list of 31 approved “casino towns” in England and Wales where licensed gaming would be permitted. The list included Westminster, Kensington and Camden, but did not include Luton. The omission proved controversial, and despite a petition signed by 20,000 residents, Cesar’s Casino was ordered to close.

Alderman Hedley Lawrence – a churchman, non-gambler and influential figure on the council – expressed frustration at the ruling. “Gambling is a mug’s game,” he admitted, “but we have to accept the fact that there is a public demand for gaming facilities. If we are not on the approved list of gaming centres, a very large number of people are going to be deprived of something they like.”

After a ten-month legal battle, Luton was finally added to the list of approved gaming towns and Cesar’s received permission to reopen the casino with six gaming tables. But the licence came at a hefty price. Each table carried an annual government duty of £4,000 – the equivalent of roughly £80,000 per table today!

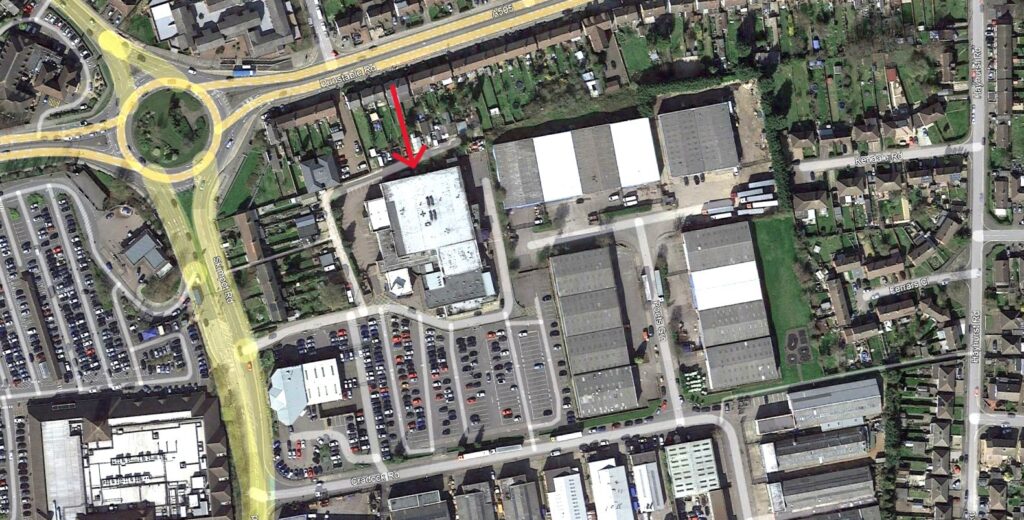

In 1972, the club was sold to Ladbrokes. In November 1973, they also purchased the adjoining greyhound stadium for £500,000 and announced it would be closing permanently. Demolition soon followed, with part of the site sold for industrial use, while the remainder was used for expanded car parking.

In 1974 Ladbrokes opened another Cesar’s Palace in Dudley, the first of several around the country. Ticket prices during the mid-1970s ranged from £3 to £5 per person, depending on the act, which included the set three-course meal. In today’s money, that would be roughly equivalent to around £30–£50.

1976 proved to be a landmark year for the club. It gained national attention after being awarded the coveted Club of the Year title, and soon broadened its programme to include professional boxing and wrestling events. That same year, the organisers of the Oxford-Cambridge Boat Race selected the club for their charity fundraising dinner, an occasion attended by Princess Margaret and American singer Jack Jones.

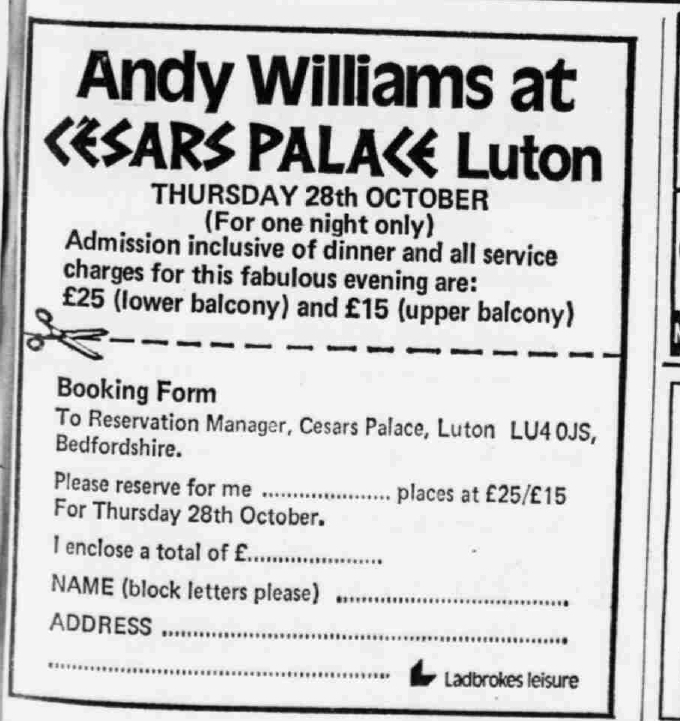

In October 1976, American singing sensation Andy Williams became the most expensive act ever booked at the club, commanding a fee of £16,000 for a single performance – a figure that had already been negotiated down from his original asking price of £27,000. At the time it was the biggest fee ever paid for a one-night stand in Britain outside of London The engagement earned him a unique distinction: he had now performed at Caesar’s Palace in Las Vegas, and also at Cesar’s Palace in Luton.

In December 1976, the club staged a Royal Gala Evening attended by Prince Philip and broadcast on BBC2. It was widely reported as the first time the Duke of Edinburgh had spent an evening in a nightclub, and at one point he was seen singing along to the Peters and Lee’s hit Welcome Home.

In 1978, a major £750,000 extension was completed and officially unveiled by Roy Castle, who joked: “They wanted Charlton Heston to perform the opening ceremony, but he couldn’t make it – so here I am.” With the new expansion in place, the club now occupied an impressive 27,000 square feet and could accommodate 1,200 guests.

Throughout the 1970s, the club thrived and quickly established itself as one of Britain’s premier cabaret destinations. It was packed 7 nights a week and coach parties traveled from across the country, drawn by a programme of headline performers that read like a Who’s Who of the entertainment world. Many of the biggest names returned year after year. Tommy Cooper, who had headlined the opening night in 1966, became a firm favourite and appeared an average of three times a year for the following eighteen years. He usually stayed overnight at the nearby Esso Motor Hotel, now known as the Chiltern Hotel.

But it was the Barron Knights who ultimately clocked up the most appearances. They were a reliably crowd-pleasing act, known for mingling with audiences before and after their sets – a personal touch that often helped ensure full houses. Their close proximity also worked in the club’s favour: they all lived just ten miles away in Leighton Buzzard so their travel costs and expenses were minimal, which almost certainly made their fee more manageable than comparable touring acts.

But just ten years later, the boom years were starting to fade. George Savva left in 1977 to open his own nightclub in South Wales and new manager Keith Broadhurst took the reigns. To try and boost attendance, Ladbrokes unveiled plans in 1979 to bring up overseas tourists from London’s West End. A programme of special “tourist shows” operated Sunday to Wednesday evenings with return coach travel, dinner and a two-hour show priced at £14.50. But the scheme failed to attract the expected numbers and was ultimately scrapped.

By 1980 attendance had declined sharply and the club was now open just three nights a week, a move blamed on the recession and rising unemployment in the local car industry. In May of that year, Ladbrokes sold the Cesar’s casino for £2.2 million to Lonrho, the conglomerate headed by Roland “Tiny” Rowland, though they continued to operate both the cabaret venue and bingo hall.

In January 1981, Ladbrokes made a shock announcement: the club had been operating at a loss for the past two years and they were now looking to dispose of it, adding bluntly, “We don’t subsidise our units.” It was said to be losing thousands of pounds a week. “We lose £4,000 on a good night” said one manager.

A series of cost-cutting measures soon followed. Thirty-four staff were made redundant and the resident band was reduced in size, prompting a dispute with the Musicians’ Union. Despite these efforts, the situation did not improve, and the club closed its doors in June 1981, resulting in the loss of around 100 jobs.

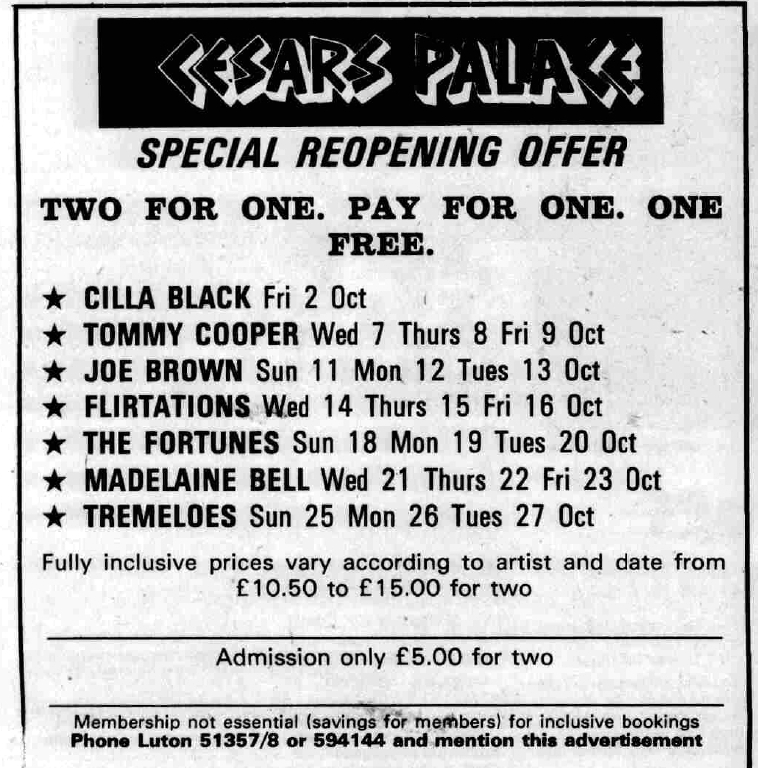

The club was next leased to a company called Highrustic, headed by Terry Russell and Jim Maddison, and reopened in October 1981. However, the relaunch brought little comfort to former staff. The new operators announced, rather bluntly, that “we plan to be selective and envisage very few of the former full-time employees being offered jobs by us.” They also confirmed that the long-standing arrangement of booking entertainment through London Management would be abandoned in favour of handling bookings directly themselves.

Television personality Cilla Black had been secured as the headline act for the relaunch, but the evening became memorable for all the wrong reasons. After completing her performance, she left the building immediately, rather than staying for the planned aftershow celebrations. She had been expected to pose for press photographs, cut a ceremonial cake and join a champagne toast, but instead made a swift exit. Her abrupt departure reportedly left management, journalists and fans furious.

The new regime unraveled almost immediately. Maddison departed after only a few weeks, leaving Russell solely in charge. After just four months, the club closed abruptly amid talk of bounced cheques, internal disputes and the walkout by the resident bandleader. Matters escalated further when Russell was alleged to have “stripped the club bare” during an overnight raid. Police later confirmed that numerous fixtures – including seating, tables and electrical equipment – had disappeared. The club’s estimated debts stood at around £500,000.

A new operator emerged a few months later when the lease was taken over by Showstopper Promotions, a “fast-expanding London-based entertainments company.” The new owners announced their intention to reposition the venue towards a younger crowd, noting that historically the clientele had been predominantly over 30.

As part of the rebranding, the old cabaret room was divided into several smaller themed bars, signifying a shift away from the traditional supper-club format. After being closed for 10 months the venue reopened in December 1982 under a new name: The Pink Elephant Fun House. Initially the change appeared successful, and the following year they even reintroduced occasional cabaret acts along with daytime events aimed at families and children.

But the attempt to attract a younger audience soon created new problems. Reports of disorder increased sharply, with local residents complaining of vandalism, late-night disturbances and fights spilling into nearby streets. Police were called to the venue with growing regularity, and the club’s reputation took a nosedive.

Attendance declined and, in a last ditch attempt to revive fortunes, it was renamed as the New California. The effort failed. In February 1986 the council revoked the venue’s licences and it closed down. With 22 years still remaining on the lease, the property was placed back on the market – but without permission to sell alcohol, host live acts of more than two performers or even allow dancing, any prospective tenant faced an uphill battle. The council indicated it might reinstate the licences, but only for a new operator.

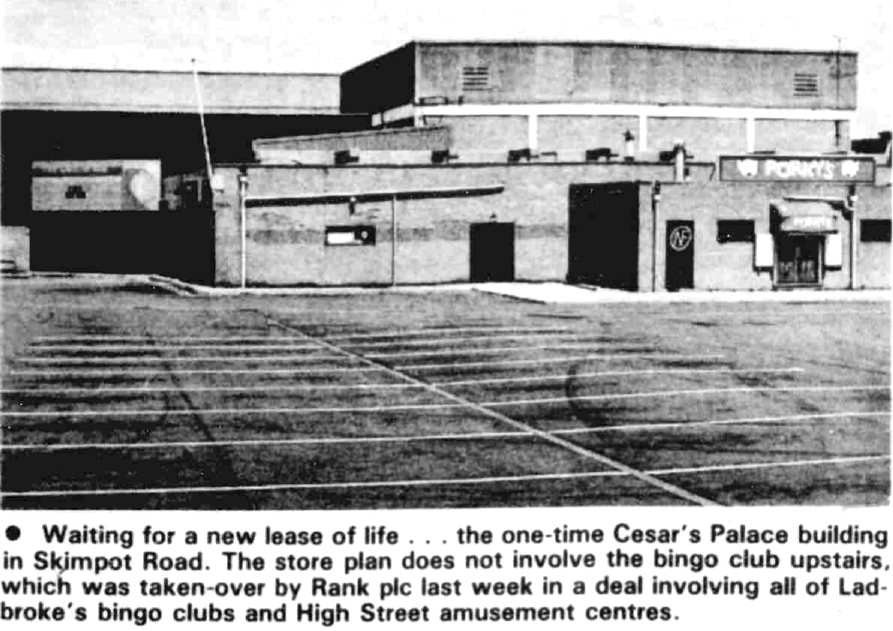

In June 1986, Ladbrokes sold the upstairs bingo club to Rank and were considering converting the main caberet venue into some kind of retail establishment – they had recently acquired the Texas DIY superstore chain.

But a more promising development came in December 1986 when the lease was acquired by Bob Wheatley, owner of the Circus Tavern in Purfleet. Wheatley was able to reinstate all the licences and appointed his son as manager. After an 18-month closure and a refurbishment costing £750,000, the club reopened in October 1987 with a performance by The Shadows. The venue also reverted to its former name, though now spelled Caesar’s Palace rather than Cesar’s Place.

The revival began strongly. Within its first 13 weeks the club generated a £1 million turnover. But at the end of 1988 the business was showing a loss of £433,000. Wheatley began subsidising operating costs from his other enterprises. When a bank withdrew financial support, the club was forced to close in January 1990 with debts of £1.75 million.

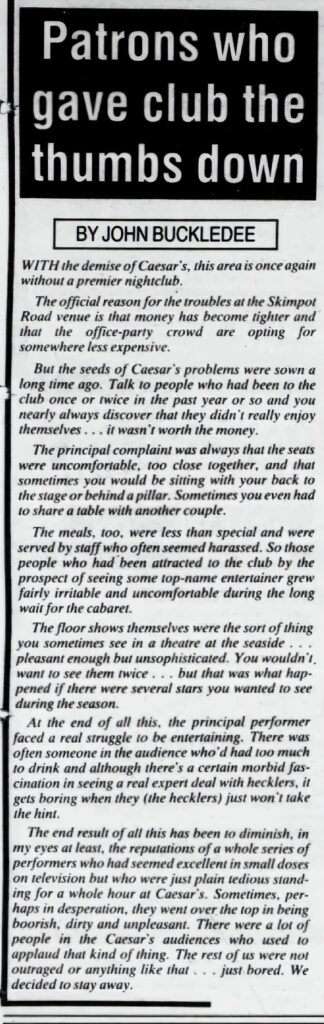

At the creditors’ meeting it was acknowledged that the pool of cabaret acts capable of filling the venue was shrinking year by year, while those still able to draw large crowds were demanding increasingly higher fees. Paying a headline performer £8,000 to £12,000 for an hour’s work had become the norm. Some commanded even more: Cliff Richard received £125,000 for five consecutive shows in April 1989. Despite the eye-watering figure, the club reported an overall profit of £100,000 from the deal, thanks largely to the higher-than-normal £40 ticket prices.

But it wasn’t just Caesar’s that was suffering. During the 1980s and 1990s, Britain’s cabaret scene saw a dramatic downward shift. Back in the day, these large clubs had thrived and attracted couples, works outings and coach tours by the dozen. By the mid-1980s audiences were no longer looking for the same kind of entertainment, and younger people were shifting more towards nightclubs, live rock venues and themed pubs. Just a few months after Caesar’s had closed, Wheatley was also forced to put the Circus Tavern into receivership.

At the same time, new forms of entertainment – stand-up comedy, alternative comedy clubs and big arena tours – offered competing ways to spend leisure time. Many cabaret clubs also struggled to modernise. Their format, food and décor remained firmly rooted in the 1970s, and what once felt glamorous increasingly appeared dated. By the 1990s, only a handful of cabaret venues remained in anything close to their original form.

Despite the downward trend, there was still no shortage of determined entrepreneurs convinced they could turn the tide and return the venue to its former glory. The next to try was Welsh farmer Clive Preece, who took on the lease and reopened the club in November 1992 – almost three years after its last closure. Confident in his vision, he told reporters: “I have visited Caesar’s Palace many times over the years and I want to bring back the good old days. I wouldn’t be spending out this kind of money if I didn’t believe I could.”

Admission was set between £20 and £25, which included a four-course meal. The original kitchen was ripped out and replaced with new equipment, along with what Preece described as “top-class chefs to ensure the food is excellent.” Drink prices were deliberately kept lower than those of comparable venues, with a pint of lager costing £1.80 and a bottle of house wine priced at £7.

The relaunch began with a high-profile charity gala headlined by Jim Davidson, although the event failed to turn a profit and no donation was actually made to charity – this was blamed on Davidson demanding an appearance fee of £7,250. Unfortunately, this proved indicative of what was to come. Attendance remained inconsistent and the club struggled to attract paying customers. Performances were frequently cancelled at short notice when ticket sales were poor, leading to several acts taking legal action over unpaid fees.

In a bid to keep the venue lively and boost bar revenue, management began handing out free entry tickets to local residents. Even so, the strategy failed to generate the income needed, and the financial situation continued to deteriorate.

Within just three months, the club had collapsed yet again – this time with debts totalling £476,000. The rapid failure underlined a stark reality: nostalgia alone was not enough to keep the doors open.

But it was certainly no deterrent, and in February 1993, it was the turn of John Blower. He had invested – and lost – £300,000 during the George Preece era and was granted the lease in order to hopefully recoup his investment. Legendary former manager George Savva – who had run the club during its first ten years – briefly returned, only to resign three months later.

The club appeared to be back on track and attracted some big names over the next two years. But behind the scenes the venue had gained a reputation for continuing with the old policy of cancelling shows at short notice This resulted in many performers boycotting the venue, or demanding payment in advance. One booking agent even urged Equity to warn its members against appearing there. It was raided by bailiffs in May 1995 for unpaid rent and closed down shortly after.

A more stable future finally seemed possible in October 1995 when the Mean Fiddler Association — a respected company with a portfolio of successful London venues — took over the lease. Their first decision was to give the troubled venue yet another new identity: The Palace. They scaled back on the old supper-club format, preferring instead to sell tickets and food separately, although a few tables were still reserved for the old-style set menu.

In January 1997, the club unveiled a new weekly event called High Spirit, promoted as a fresh concept in club culture and featuring top DJs from around the world. However, the shift in direction was not welcomed by everyone. The adjoining casino complained that the venue had transformed from an “established nightclub to a rave club,” which, they alleged, had brought with it “a significant increase in noise, vandalism and severe traffic congestion.”

Customers trying to call the venue to ask about upcoming events were also growing increasingly frustrated. One complained: “If you ring up The Palace they tell you to ring a Mean Fiddler number in London. If you ring Mean Fiddler they tell you to call The Palace. It’s daft.”

Also that year a local newspaper discovered that the club had secretly been put up for sale.

The club finally closed its doors for good in 1998, bringing to an end a turbulent 32-year history. The bingo hall upstairs, sold to Rank in 1986 and later rebranded as Mecca Bingo, continued to trade and eventually Rank acquired the entire building. It was subsequently remodelled into one huge large-scale bingo venue complete with slot machines, bars and restaurant facilities.

Mecca Bingo Luton remains open today and still hosts occasional live entertainment, though nothing approaching the scale or star power of the performers who once took the stage at Caesar’s during its heyday.

We’d love to hear your memories and stories about Caesar’s Palace. Please feel free to leave a comment below.