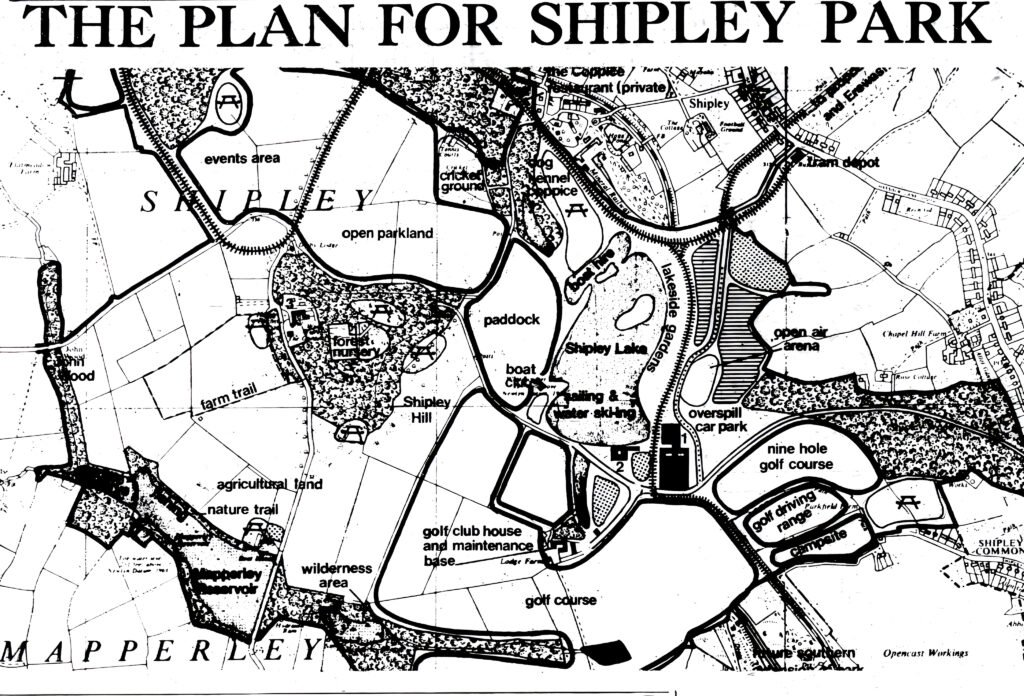

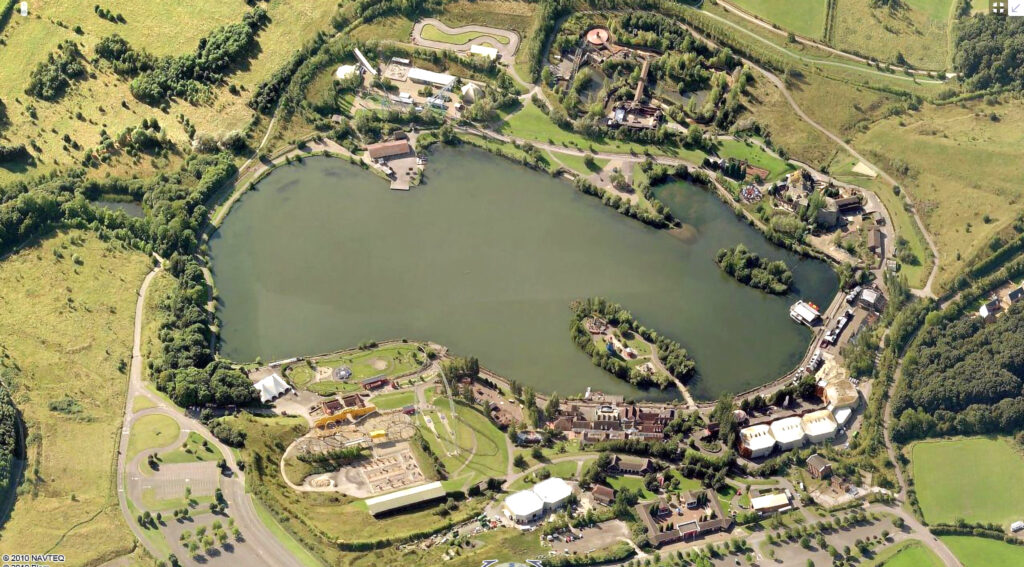

During the early 1970s a large open cast coal mine near Ilkeston was cleaned up by Derbyshire County Council and turned into a 1,000 acre country park which opened to the public in 1976. Known as Shipley Park the site featured miles of pathways, cycle ways and bridle tracks with woods, lakes and picnic areas.

A third of the site was earmarked for a zone of “intensive activity”, in other words, some kind of leisure or tourism facility. Various ideas were thrown around including a golf course, conference centre, hotel and ski slope. Early maps showed a sporting arena and a tram running alongside the lake.

A brief history of Tucktonia

Harry Stiller, whose father invented the well-known 1001 carpet cleaner, came from a wealthy background. In his younger years he pursued a passion for motor racing, going on to win the Formula Two European Championship.

In the early 1960s he purchased the Tuckton Golf Course in Bournemouth and transformed the land into a family leisure park. Attractions included a boating lake, swimming pool, miniature railway, and a range of amusement rides. The former clubhouse was converted into a pub, aptly named The Golfer’s Arms.

In 1975 the site was sold to Grand Metropolitan, though Stiller remained involved as an advisor.

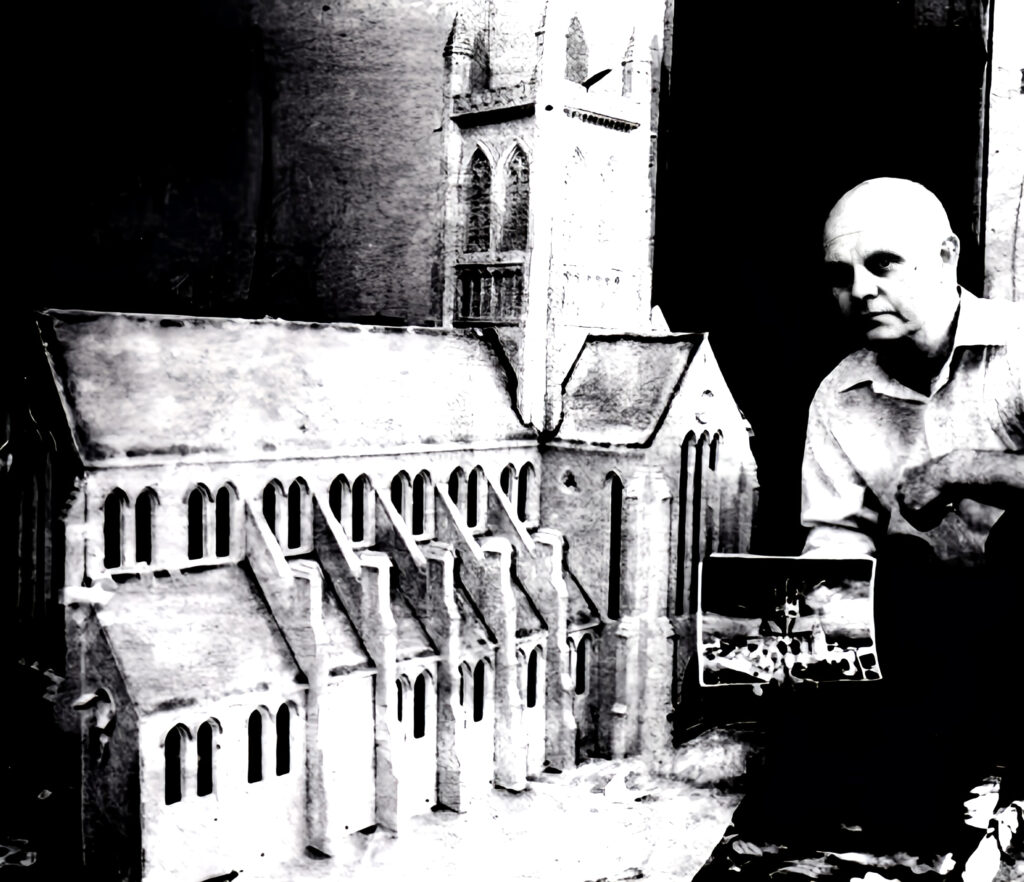

One of Harry Stiller’s long-held ambitions was to create a model village, and this dream took shape in 1976 when Grand Metropolitan invested £850,000 into building a 3.5-acre attraction called Model Land. Billed as the largest of its kind in Europe, it showcased a “Best of Britain” theme, with everything constructed to the generous scale of 1:24. Among its highlights were a 14-foot model of St Paul’s Cathedral and a 26-foot replica of the Post Office Tower.

The design and construction contract went to a local Bournemouth company called KLF, run by Peter Kellard, who subcontracted all the modelmaking. 30 buildings were produced by model maker Don Lawrence.

The project proved successful, but in the mid-1980s the park closed after the land was found to be worth £10 million. The site was later redeveloped for housing and is now occupied by The Meridians estate in Christchurch.

Britannia Park is born

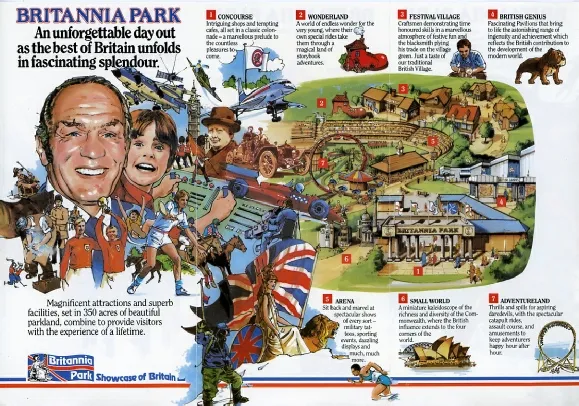

After the success of Tucktonia, Peter Kellard turned his attention to Shipley Park. He arranged a meeting where he proposed a theme park based on the ‘Best of Britain’ where the country’s genius and ingenuity could be celebrated. He wanted the park to have a strong educational theme as opposed to having lots of thrill rides. He made bold claims that it would become the UK’s top tourist attraction.

Kellard also said that he planned to build a model village in the new park, similar to what he’d done at Tucktonia. It would feature buildings from 35 different countries, mainly those connected with the old British Commonwealth. And he would call his new venture Britannia Park.

The council liked the idea and an agreement was drawn up.

In 1980 a contract was signed with the council, granting Kellard a 90-year lease on 350 acres of land. The deal included a £1 million investment from the council in return for annual rent plus a share of income from any sub-tenants within the park. Planning permission was then sought – by the council from itself – and unsurprisingly approved. With everything seemingly in place, KLF announced that Britannia Park would open in 1982.

However, opposition quickly emerged. A local pressure group, The Friends of Shipley Park, launched a fierce campaign against the project. They submitted 1,250 letters of objection and gathered a petition of 5,000 signatures, arguing that the planning permission was invalid. In February 1981 a judge at Nottingham High Court agreed, and the application was quashed.

In May of that year KLF faced another setback when Labour replaced the Conservatives at Derbyshire County Council. The new council leader, David Bookbinder, was a firm opponent of the Britannia Park scheme and sought to renegotiate the lease. What had once been a cordial relationship with the council quickly soured. Yet there was little Bookbinder could do – the new council had inherited a signed contract that bound them to the project. Frustrated, he became a “hostile partner,” determined to make progress as difficult as possible.

Fresh objections soon arrived from the highways department and the parish council, leading to further disputes and legal wrangling. Over the next two years the project became mired in court battles, with planning permission finally secured in 1983 – though not before yet another visit to the High Court.

1984: Construction finally begins

Construction finally got underway in late 1984, with a total of £9 million poured into the project. Half of that sum came from bank loans, while a further £1 million was contributed by the council. The remaining £3.5 million was provided by contractors – many of whom were still awaiting payment.

Britannia Park finally opened its gates on 27th June 1985. Yet even on opening day, Councillor Bookbinder continued his campaign of opposition. He made it clear he did not want an invitation to the ceremony, and went so far as to ban 600 schoolchildren from attending and singing Rule Britannia, declaring that it was not an educational activity and that the children were being “exploited” by the company.

The move was widely condemned. Amber Valley MP Phillip Oppenheim described it as “the most petty, mean and small-minded action by the county council to date.” Bookbinder also ordered all publicity material for the park to be removed from Derbyshire libraries.

On the eve of opening, fire safety officials visited the site after receiving an anonymous tip of “serious shortcomings.” The park was inspected an given the all-clear. One letter to the local press summed up the mood: “What a great pity Councillor Bookbinder and his fellow councillors behaved so destructively over the opening of Britannia Park.”

Rumours had circulated that a member of the royal family might attend the opening ceremony, but instead the event was graced by the presence of boxer Henry Cooper, who also agreed to appear in a television advert for the park. Adding to the spectacle, Concorde flew up from London with a planeload of VIPs and performed three impressive flyovers above the site. Marching bands, clowns, and morris dancers entertained the crowds.

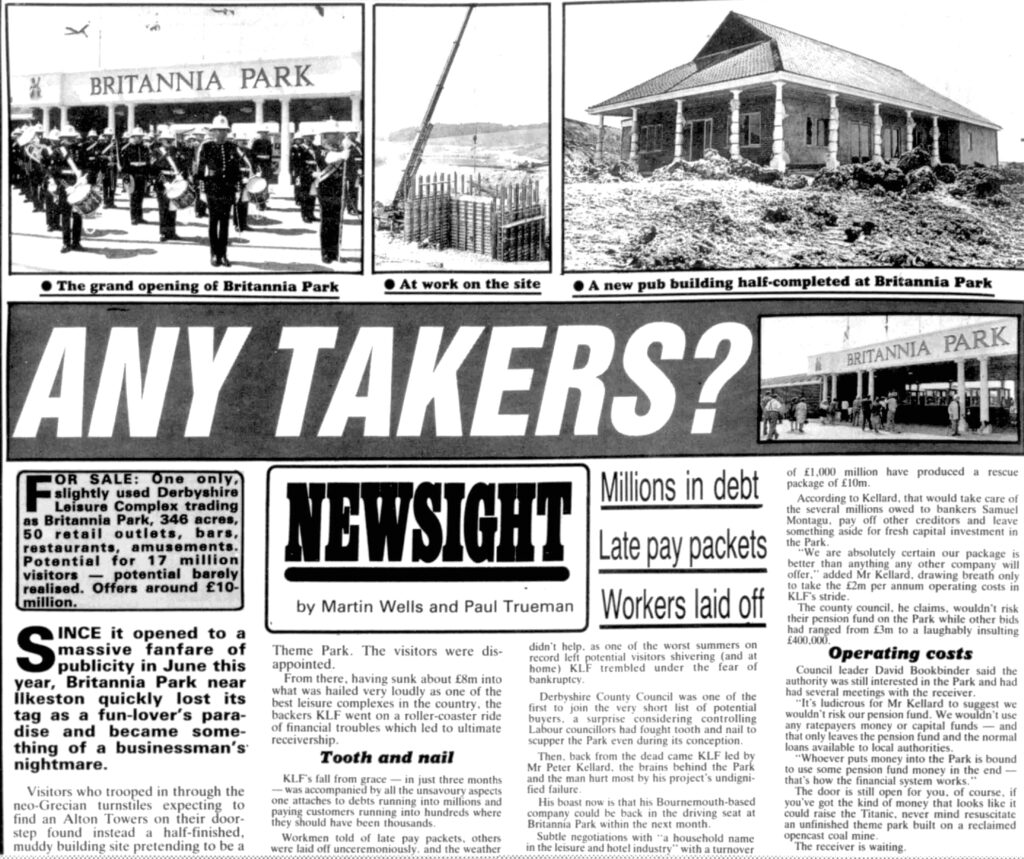

Unfortunately, it quickly became clear that Britannia Park had opened prematurely. Pressure from the banks had forced the early launch, and on opening day lorries and JCBs were busy moving around the site. A local newspaper observed: “Visitors expecting to find an Alton Towers instead found a half-finished muddy building site pretending to be a theme park.”

Many of the promised attractions were incomplete. The British Genius exhibition, billed as the park’s centerpiece, was unfinished, as were the model village and miniature railway. One visitor remarked that the entire park could be seen in “less than an hour.” Within a week, the £3.50 adult admission fee was reduced to £2.

But by the end of July, most of Britannia Park’s attractions were operational and a host of summer events were scheduled. The adult ticket price was restored to £3.50. In early August, the park held a free admission day, drawing a crowd of 30,000 visitors. The event caused major traffic jams, and staff struggled to find parking for the 8,000 cars on site.

The long-awaited British Genius exhibition finally opened, featuring waxworks and dioramas of notable figures such as Sir Isaac Newton, Shakespeare, and Queen Elizabeth I. The display also showcased cars, planes, and inventions from across the ages. A full-scale reconstruction of Downing Street included Churchill’s original wartime car.

The £120,000 miniature railway was in operation, featuring a diesel locomotive and carriages that had previously run at the Liverpool Garden Festival the year before. The craft village was fully occupied, with 32 different vendors showcasing their wares. An arena with a covered 2,000-seat grandstand had been constructed. However planning permission for a Huss Condor ride and the UK’s longest slide were rejected.

The Friends of Shipley Park remained vocal in their opposition. One member wrote to the local paper, recalling the land as “rolling fields, hills and lakes.” A respondent countered sharply: “I’d need to be 300 years old to remember all that. I’m a pensioner, and all I can remember is filth, slurry and pit hills.” He went on to argue that Britannia Park should be applauded for “converting a few acres of utter wasteland into a pleasant retreat.”

A local newspaper columnist, who had previously been critical of Britannia Park, visited in mid-August and was “pleasantly surprised at just how good it all was.” He added, “I’m convinced that, given half a chance, this 350-acre potential paradise can become second to none.”

Some 15,000 paying visitors attended over the August bank holiday weekend, although a planned pop concert had to be cancelled after the park failed to give the council sufficient notice.

Despite these numbers, and despite the mostly positive reviews, the season was a major disappointment. It wasn’t helped by having the wettest summer for 20 years. It was thought the bad publicity caused by the chaotic opening day had deterred many potential visitors and attendance fell well short of predictions

The receivers are called in

On 10 September, Britannia Park called in the receivers. Some leased attractions were returned to their owners, though the remainder of the park remained open. In a surprising turn, Councillor Bookbinder softened his stance, expressing interest in taking over the site and describing it as “a place of beauty.” He added that he held no personal grudges over the prolonged disputes with the previous owners, noting, “We are sad that a lot of people have staked a lot into that park.”

The scale of the financial collapse soon became clear: 609 creditors were owed a total of £9.3 million. Henry Cooper had not been paid for his involvement, nor had Concorde. A local construction company responsible for much of the landscaping was owed £500,000.

Many businesses suffered devastating losses. Don Lawrence, who had built numerous models for both Tucktonia and Britannia Park, once operated two factories employing 30 people. The collapse forced him to sell his business, his home, and his car—and he never even recovered any of the models he had built.

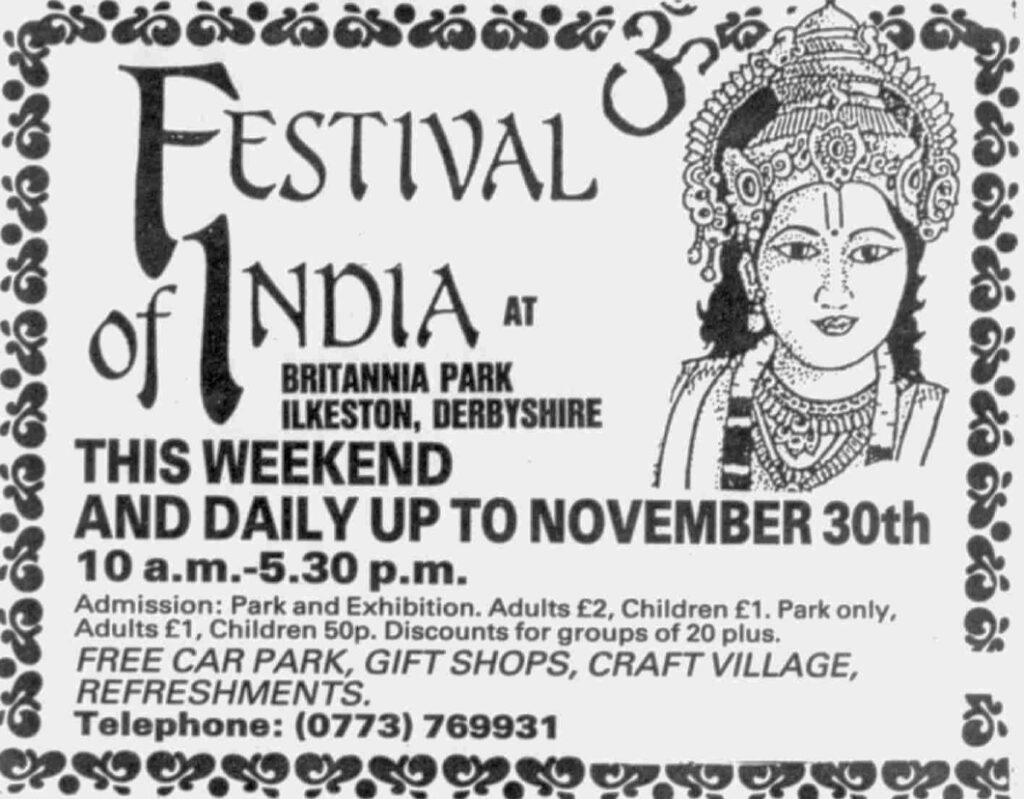

The receivers allowed the park to remain open until the end of November to accommodate a planned Festival of India exhibition, which had previously been a major success at Alexandra Palace in London. By this stage, however, the only attractions still operating were the craft village and a few gift shops.

There was talk of trying to keep the park open through the winter but it finally closed for good in early December, just 5 months after opening.

The following Easter the craftsmen returned and went back to work in the craft village. The receivers wanted them out so they could sell the park with vacant possession. They refused to leave so the power and phones were cut off. They staged a sit-in protest. A deal was later reached (they were each offered £4,000) and they agreed to leave by June, and the power and phones were reinstated.

Following a 17-month trial-the longest in British history at the time-Peter Kellard was sentenced to four years’ imprisonment, while John Wright, Chairman of Britannia Park, received six months. Remarkably, the cost of the court case exceeded the park’s total debt. One witness was even flown in from Canada and accommodated in a hotel for several days, solely to testify that Kellard had once discussed opening a park in Canada.

The council buys the park

In June 1986, the council purchased the site for £2.5 million. The following month, a deal was reached with Park Hall Leisure, part of the Granada Group, forming a new company called Shipley Park Ltd. The six-member board included three council representatives and three from Granada.

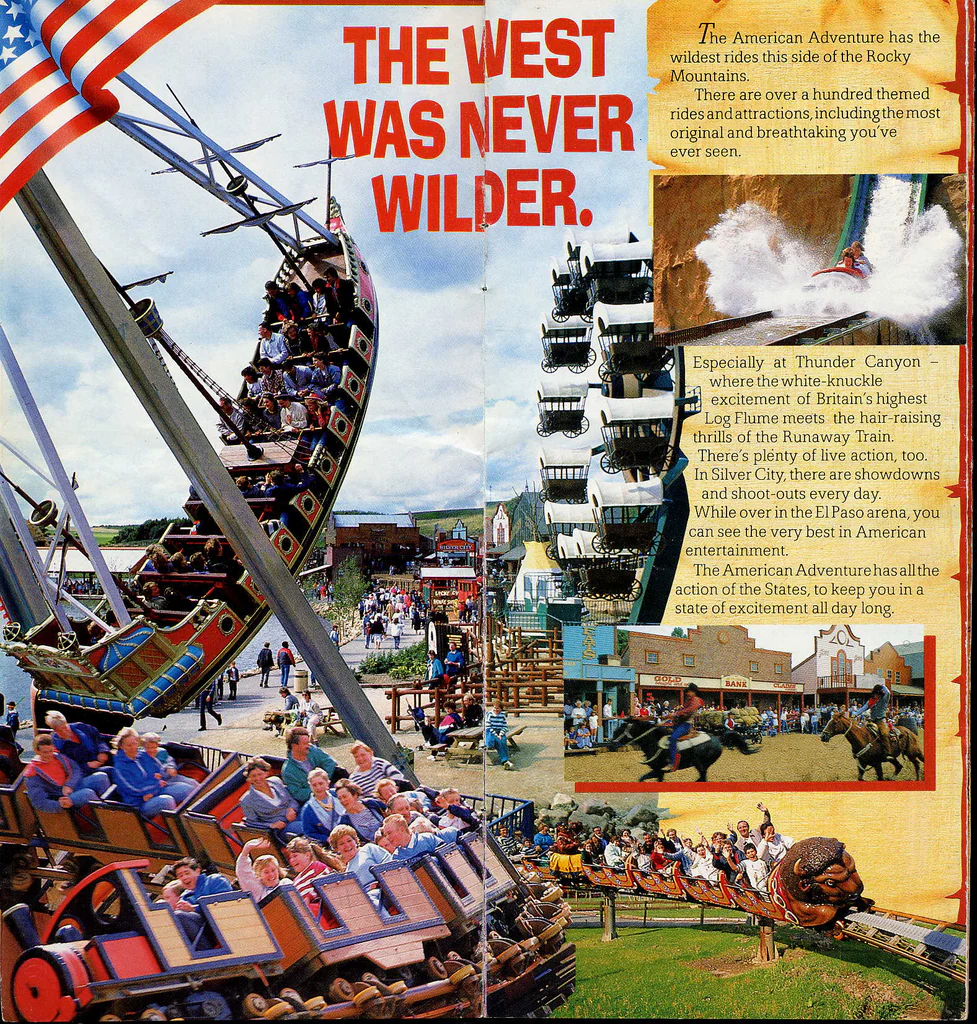

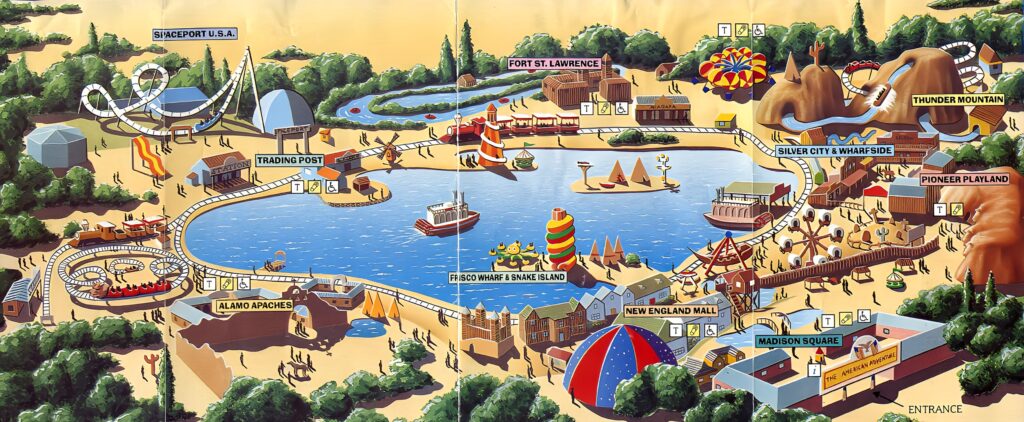

Granada paid £1.5 million to take over the lease and pledged to invest £7.5 million in the first season. The original educational theme was abandoned in favor of a full-scale amusement park inspired by the American West. The park was initially named Silver City, but the name was later changed to The American Adventure Theme Park. John Rigby of Park Hall Leisure was appointed to oversee the development of the new park.

You can read more about Park Hall Leisure and John Rigby in our blog post on the history of Park Hall.

Rigby, along with operations director John Ellis, were put in charge of redeveloping the new park. The two John’s actually lived on site for a few months.

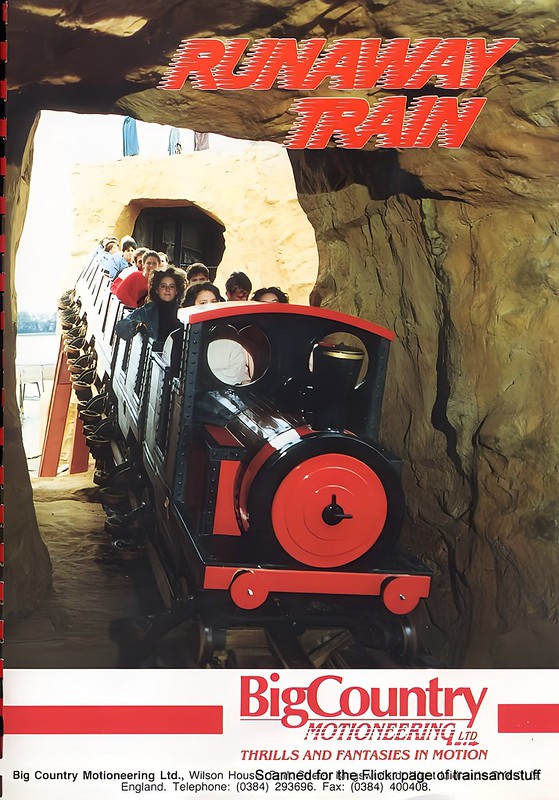

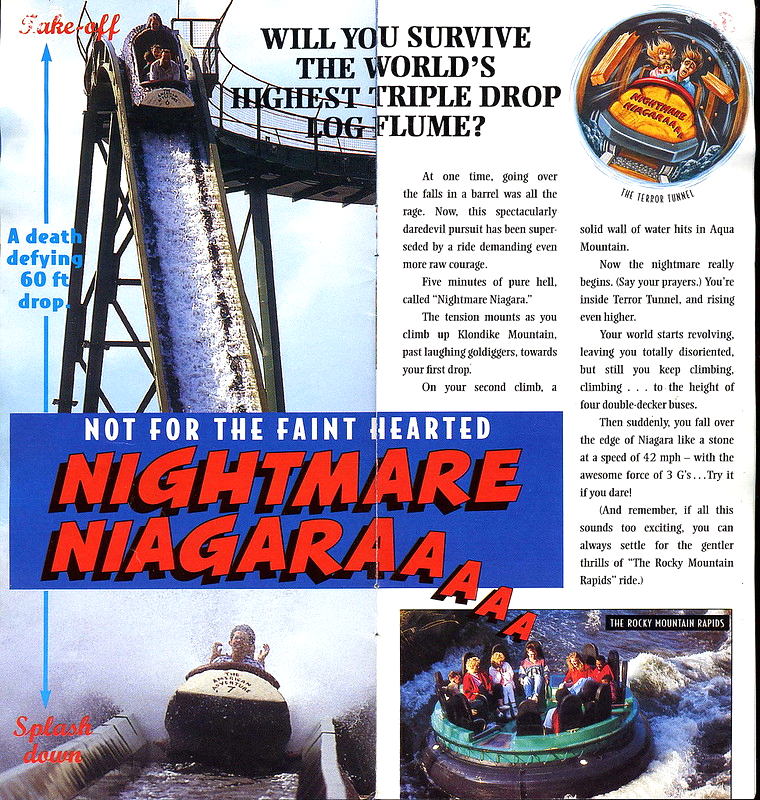

Back in 1986 Rigby had contracted with a British company called Mimafab to build a log flume at his own park at Camelot. The ride was successful, so he partnered with them again to build a bigger version at the new American Adventure park, along with a powered mine train coaster.

A brief history of Mimafab

Mimafab, based in Kirby Misperton, was founded in 1984 by Mike Anderson after he won a contract to build a monorail at Flamingoland. GMT, originally a supplier of railway equipment and rope haulage systems to the National Coal Board, sought to diversify into the leisure industry following the decline of mining. Drawing on their technical expertise, GMT started working with Anderson to design and build amusement rides.

In 1989 the owners of GMT sold the business and started a new company called WGH Transportation which was focused solely on the amusement ride business. They continued to work with Mike Anderson. Mimafab was later renamed Meridian Motion Engineering and then Big Country Motioneering. Mike Anderson remained in control of all three.

At some later stage, Anderson also became involved with a company called Interlink. It all gets a bit complicated but between 1985 and 1990, the combination of Anderson, GMT, WGH, and Interlink produced numerous rides, both in the UK and abroad. This included seven log flumes, five mine train coasters, two miniature railways, and two river rapids rides. Some of this group were also involved in the construction of the Ultimate coaster at Lightwater Valley in 1991. Mike Anderson passed away in 2014.

The American Adventure Theme Park

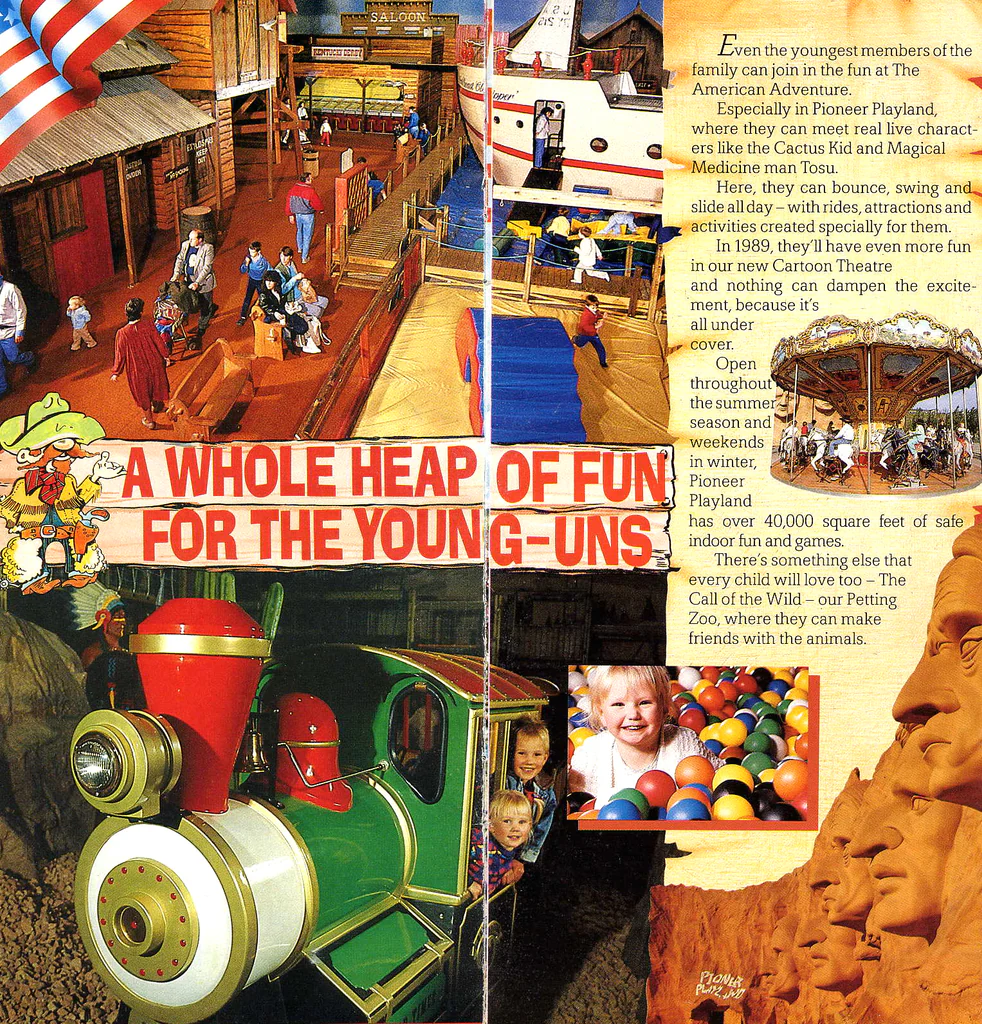

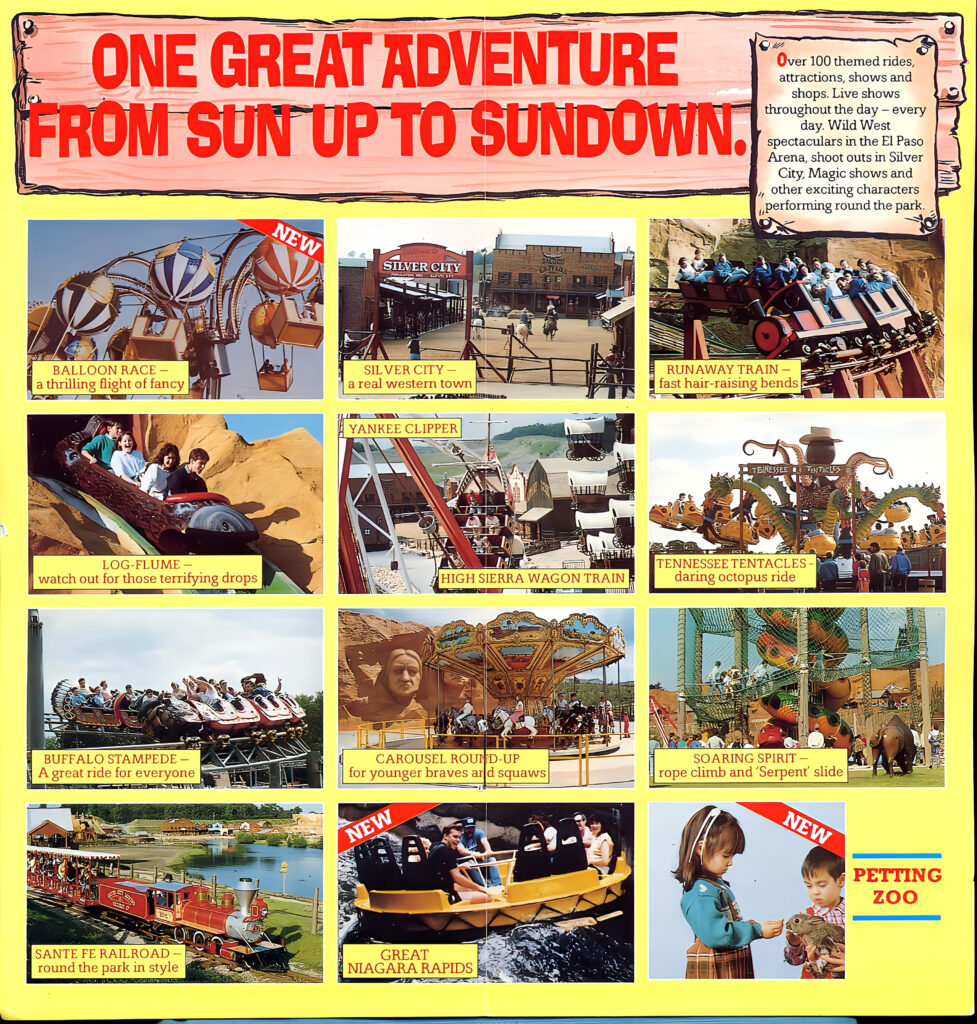

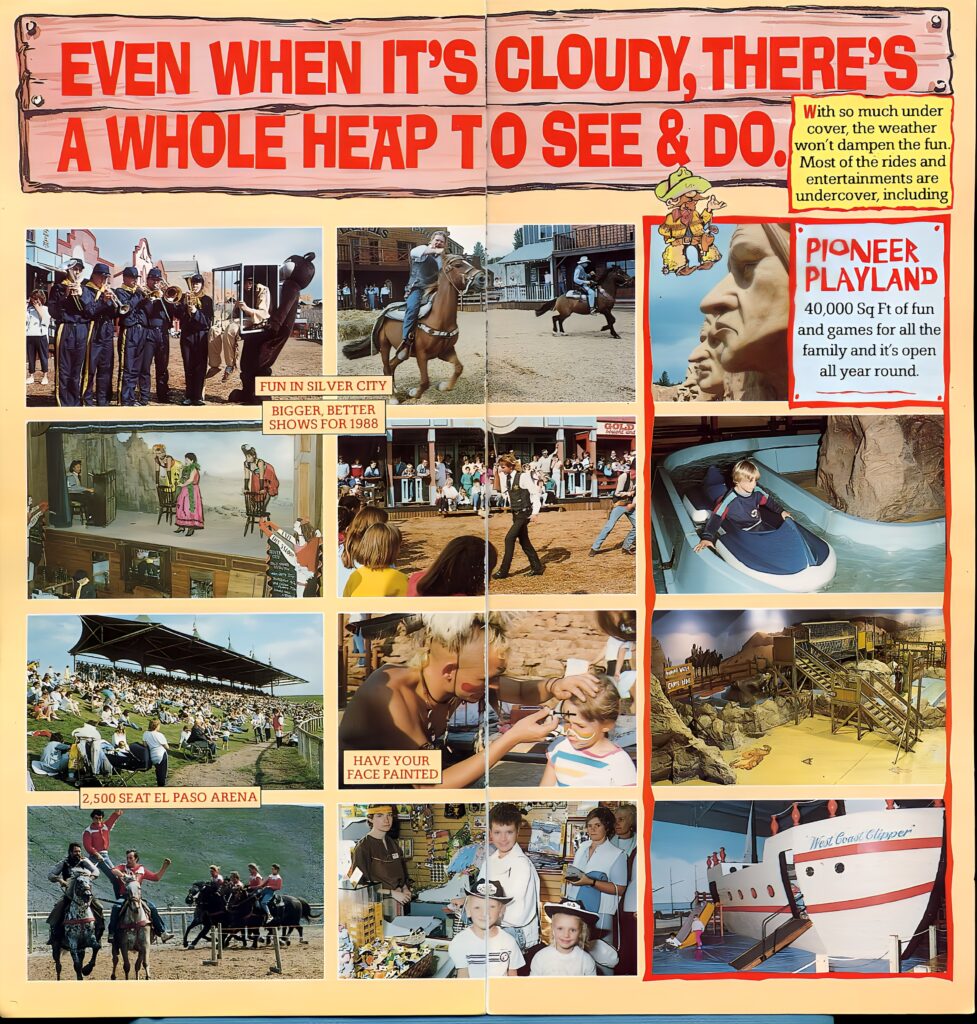

Construction of the new park was progressing well. Severn Lamb of Stratford upon Avon built two paddle-wheel boats for the lake, along with a new train for the miniature railway (the previous one had been leased). Italian company Zamperla supplied a ‘Buffalo’ roller coaster along with a pirate ship, kiddie train and Ferris wheel themed after a wagon-wheel. The former Genius building was converted into a huge indoor play area known as Pioneer Playland, the biggest in the country, featuring Mount Rushmore-style faces on the outside.

A western town was built with its own saloon bar and dancing show girls. The old Britannia Park arena was used for cowboy shows, but in 1990 it was converted into a go-kart track. 12 live buffalo arrived from Chester Zoo – one escaped and “rampaged” through nearby Heanor for several hours before being safely recaptured.

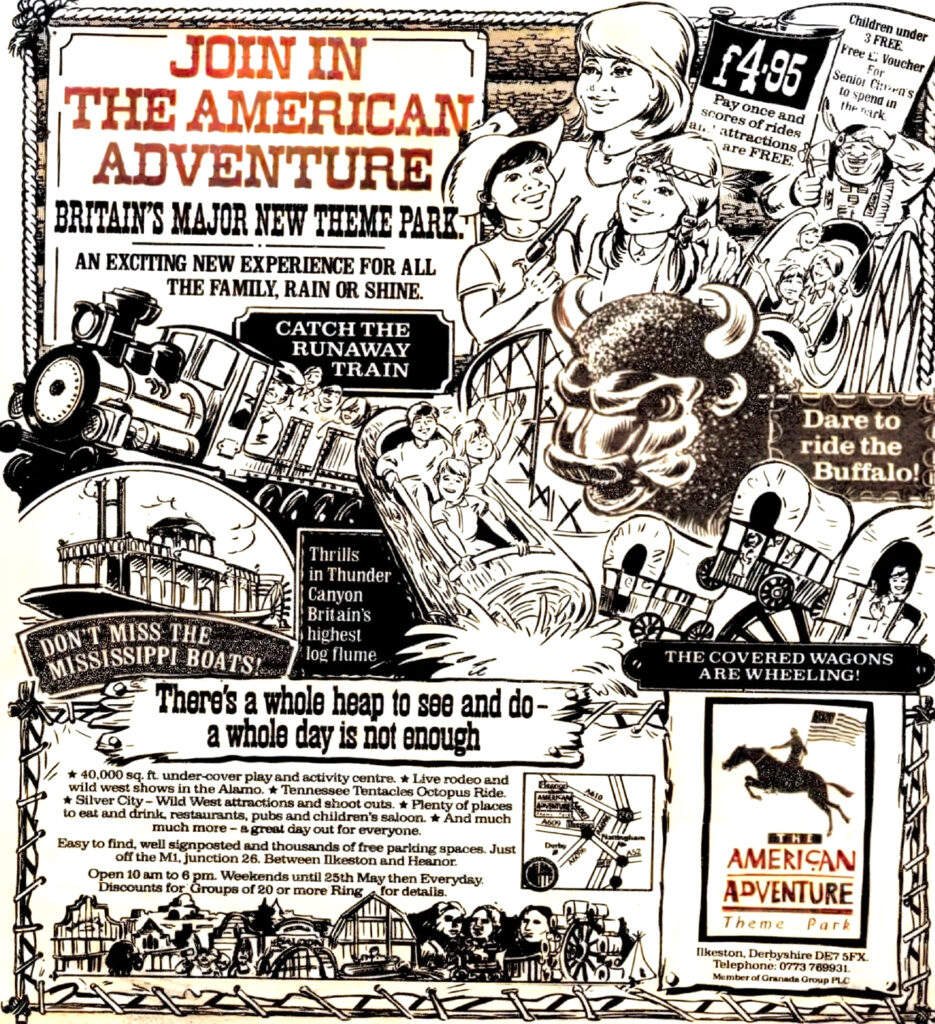

The new park opened to media previews in May of 1987 but as it wasn’t quite finished, and not wanting to repeat what happened before, it wasn’t officially opened to the public until July 1987. The official ceremony was conducted by music/TV personality Jonathan King. The park advertised itself as the only genuine theme park in the country.

The first season of American Adventure was considered a success, attracting 400,000 visitors. Adult admission was set at £4.95. That summer, a group of park employees were reportedly kicked out of Alton Towers for distributing promotional leaflets in the car park.

For 1988, a further £3.5 million was invested, with the bulk of the money going toward a new Mimafab/GMT river rapids ride, which became the UK’s largest. The ride reportedly had a monthly electricity bill of £7,000. Zamperla also supplied a balloon race attraction, and the adult admission price was increased by £1.

In May 1988 Rigby left Granada and later bought Windsor Safari Park.

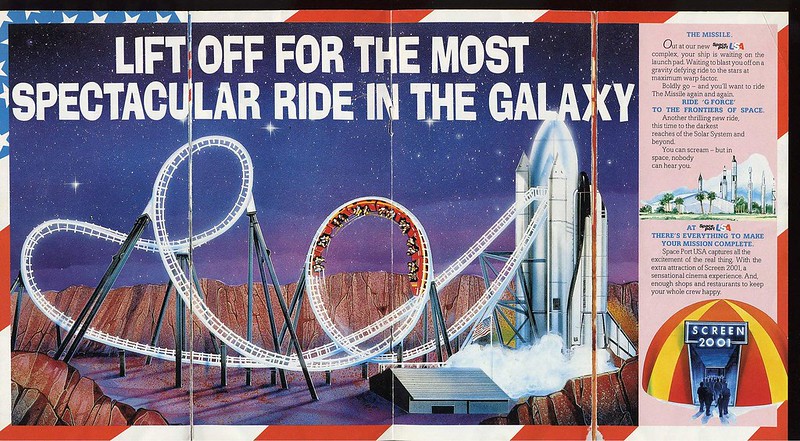

For 1989 another £4 million was invested into a new space-themed area consisting of a Vekoma Boomerang coaster and a Cine 360. The miniature railway was extended to run all the way around the lake, and Severn Lamb supplied a second train.

The Golden Era comes to a close

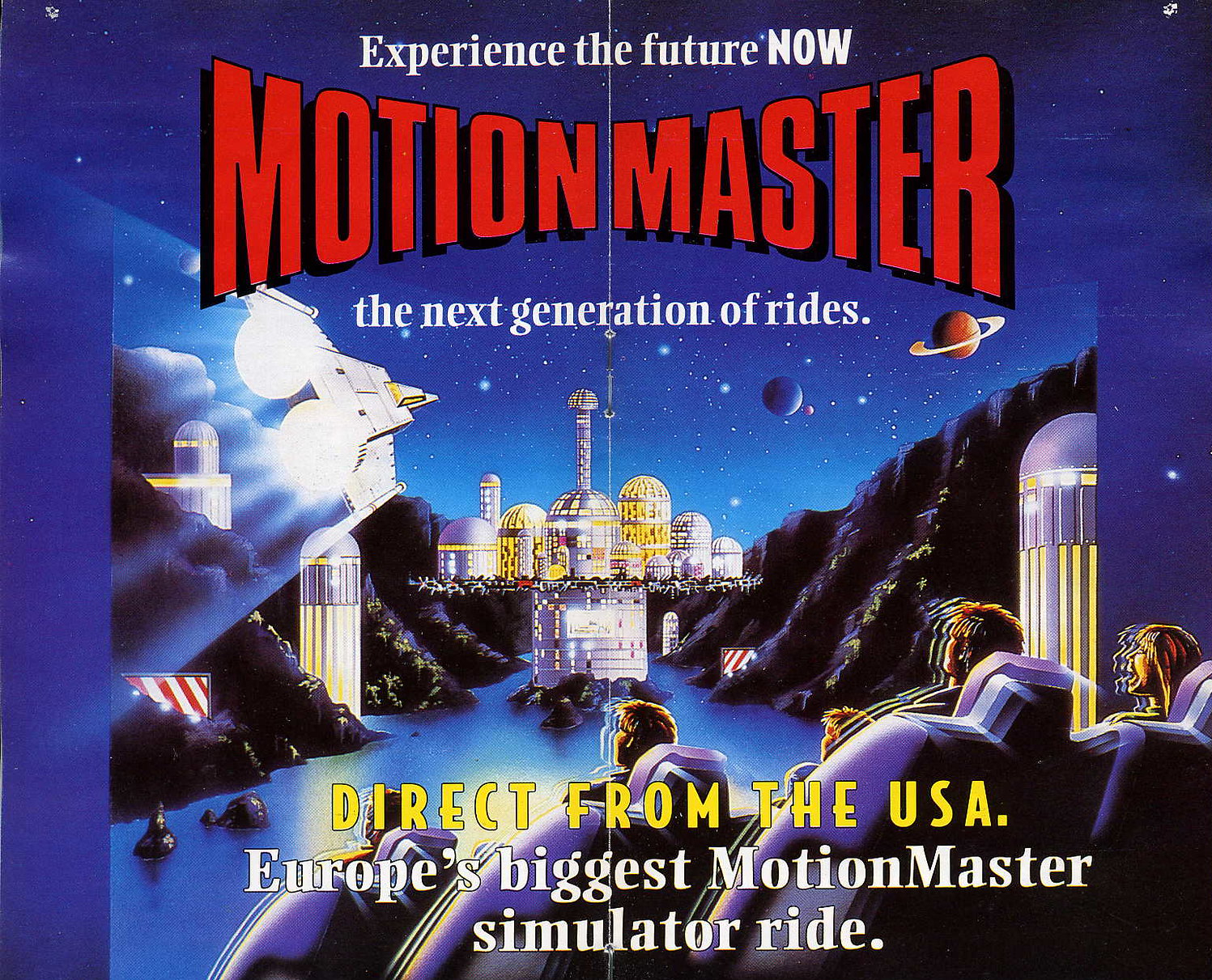

This really marked the end of the “golden era” for the park. In 1993 WGH returned and added a third drop to the log flume, making it the highest in the country. In 1994 a Motion Master simulator opened in part of the old indoor playground. In 1995 a secondhand looping coaster was acquired from Lightwater Valley. But not much else happened over the next 6 years.

In 1996, The American Adventure enjoyed a record year, attracting 625,000 visitors. Yet compared to other parks – Chessington with 1.8 million and Thorpe Park with nearly 1.2 million – the numbers highlighted the park’s ongoing struggle. Ironically, at that time, American Adventure was arguably better than either of those competitors.

The park is sold

In 1997, Granada sold the park to Venture World, a company controlled by Trevor Hemmings – you can read more about him in our Pontins History blog. Alton Towers mastermind John Broome was brought in as a consultant and became the public face of the company. Plans were announced to invest seven figures in redeveloping the park, and the name was changed to American Adventure World.

The main entrance was relocated to a new position around the side of the park. The original entrance – a holdover from Britannia Park – led into an attractive courtyard filled with shops and restaurants, offering spectacular views across the park. By comparison, the new entrance was plain and boring. While it was officially claimed that the old entrance was suffering from mining subsidence, in reality the move was made to create a single-level layout for the park.

Venture World launched a major publicity campaign, and in their first season they added a Sky Coaster, an upcharge attraction. In 1998, they introduced the Flying Island, a moving observation tower officially opened by pop group Boyzone. John Broome left the company at the end of that year, and little else of note happened afterward.

While Chessington and Thorpe Park continued to invest and expand with new rides and attractions, American Adventure was left behind in the dust. At least the park’s maintenance remained solid, and it always looked well kept.

The following photos were taken in 2005

In 2005, American Adventure announced it would remove its thrill rides and reposition itself as a family park. The log flume, river rapids, and Boomerang coaster were all closed, replaced with several smaller children’s rides. The changes had little impact on attendance, although the river rapids was refurbished and briefly reopened in 2006. The park ultimately closed at the end of that year.

Company accounts reveal that American Adventure posted losses every year under Venture World’s ownership: £1.1 million in 2002, £1.2 million in 2003, £2 million in 2004, and £1.6 million in its final season.

The rides were sold off and the site is now being redeveloped for housing.

We’ve got lots more photos of the American Adventure so we’ll probably create another post in the near future showcasing all of our images.

We’d love to hear your memories and thoughts of both parks. Please feel free to leave a comment below.