Age of Steam was a railway-themed leisure park that opened in 1977 at Crowlas, just off the A30 in Cornwall four miles east of Penzance. Despite its ambitious beginnings, the park had a short life and closed after only eight years.

The story begins with the Shillingstone Light Railway, a private line built by Sir Thomas Salt to serve his pig farm in Dorset. First laid down in the 1950s, the railway gradually developed into quite an extensive system with more than a mile of track. Sir Thomas died in 1965, but the line remained intact – albeit largely unused – for another decade. In July 1975 the entire railway was auctioned at a Christie’s sale of vintage vehicles held at the National Motor Museum in Beaulieu.

Among the buyers were Mr. and Mrs. Webb of Penzance who purchased the two diesel locomotives along with the track and turntable. Soon afterwards, they acquired an 18-acre site at Crowlas that would become the Age of Steam park. The land was locally known as Bolton Moors, a name recalling Lord Bolton’s financial involvement in local mining ventures during the 18th and 19th centuries. It was also reputedly the site of one of Thomas Newcomen’s earliest pumping engines, while folklore maintains that the last wolf in England was hunted and killed there.

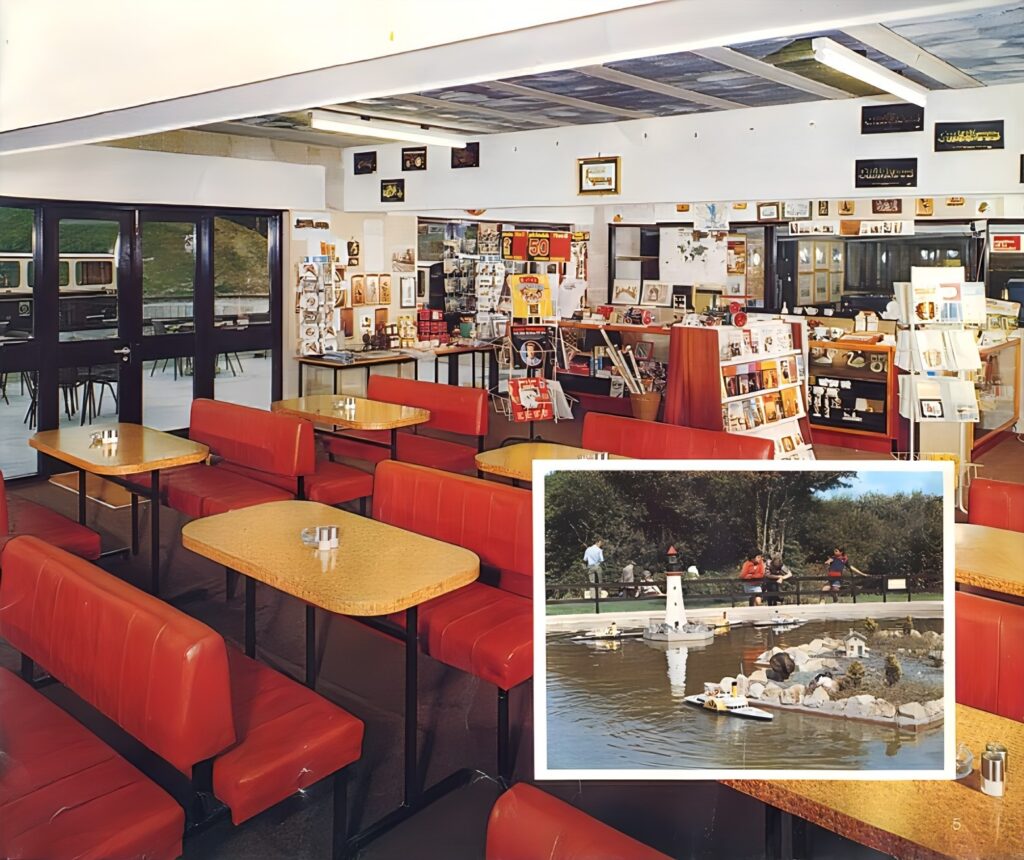

Construction of the new park began in 1976. Thousands of tons of earth were moved, and a mile of track was laid in a dogbone-shaped loop. A boating lake and pond were excavated, a car park created, and more than 2,700 trees and shrubs planted to landscape the grounds.

Promotional material described the venture as:

“Not just another steam railway, not just another model railway display. Again, not just a collection of old machinery and relics, but a professionally planned and coordinated presentation of some of the best of these elements – and more.”

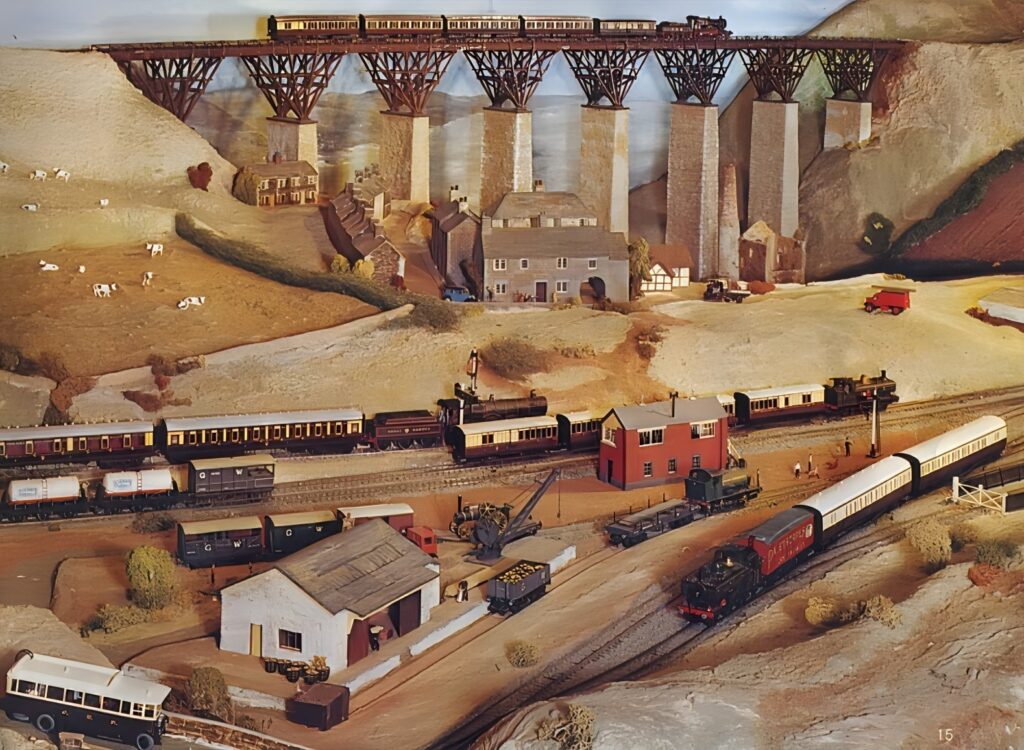

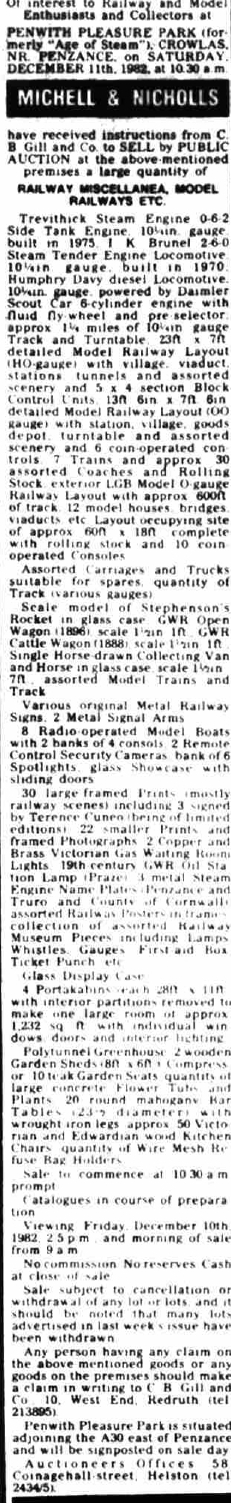

At the centre of the park stood a purpose-built exhibition hall. Inside was a OO-scale model railway depicting the Cornish GWR mainline station at Erith. A second OO layout could be operated by visitors by putting a coin in the slot. The building also contained a collection of railway relics and models, a restaurant, and a gift shop. Outside, a sun terrace overlooked the turntable, where one of the locomotives was usually displayed. Another coin-operated layout featured G-scale LGB trains, while additional attractions included radio-controlled paddle boats, a croquet lawn, and kids playground.

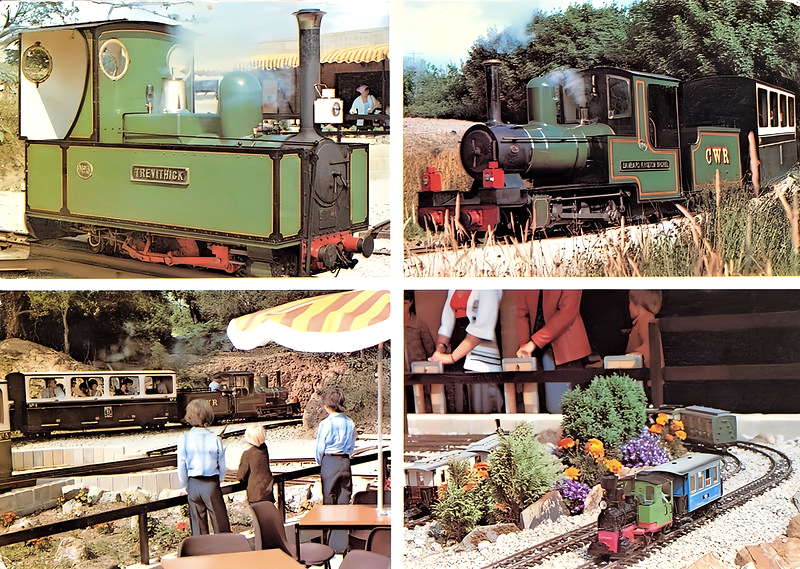

Two new steam locomotives were specially built for the line. David Curwen supplied an attractive 2-6-0 tender locomotive named Isambard Kingdom Brunel, while Roger Marsh constructed a rather less elegant tank engine named Trevithick. Six passenger carriages were built locally in Penzance.

The Webbs had ambitious plans for the future, including a second floor for the exhibition hall and an extension to the railway itself. I don’t know what happened next, but by 1981 the park was owned by Tom Lagar. He soon submitted a host of new planning applications, most of which were approved. These included an outdoor swimming pool, an extension to the exhibition hall, motorcycle and kiddycar circuits, an aviary, minature village, and helter skelter. But I don’t think any of these projects was actually built.

For the 1982 season the park had a new name – Penwith Pleasure Park – and a new attraction in the form of the country’s largest collection of vintage fairground rides.

A brief history of the fairground rides

Starting in the 1940s, Commander John Baldock began preserving steam traction engines before expanding his collection to include road vehicles, fairground rides and railway equipment. He opened the growing collection to the public in the grounds of his Hollycombe estate in Hampshire, where it became a popular attraction. However, as the collection grew ever larger, issues with planning permission and the immense cost of maintenance eventually forced Baldock to sell off the fairground rides in 1981.

The collection was purchased by Madame Tussauds, who intended to install it at their Chessington Zoo site. However, a sudden change of plans meant the rides were placed back on the market just a few months later. In April 1982, the new owners of Penwith Pleasure Park, backed by a Bristol-based finance company, raised £250,000 and acquired all the rides and everything was soon up and running at Crowlas.

But the 1982 season proved disappointing. A frustrated Tom Lagar admitted:

“It is not viable at the park; there are not enough visitors to support it. It has cost a lot of money in maintenance and repairs. Everybody screams that British heritage has to stay in this country, but no-one pays for the thing except muggins like me.”

At the end of 1982, the Fairground Association carried out a professional report on the state of the equipment. The findings were damning, noting that much of the collection was “suffering badly” after two winters left exposed to the elements. The report concluded:

“The Penwith experiment has now come to an end. Apart from the mistake of supposing that such a venture could satisfactorily take place in the open air, Cornwall is not the right place for something which must be a round-the-year enterprise if it is to pay its way.”

Following this assessment, the rides were dismantled and moved into undercover storage at Hayle while awaiting a new owner.

In December 1982 the entire contents of the park were out up for auction, this included the miniature railway, the model railway layouts, all the museum exhibits, and the contents of the restaurant – literally everything.

I’m not sure what happened next – was the auction cancelled? But the park appears to have reopened again in 1983 and again in 1984, minus the fairground. During 1983 Lagar applied for planning permission to build 40 holiday chalets on the site, but the application was refused.

The park seems to have closed for good at the end of the 1984 season. Soon after, the railway tracks were taken up, the trains removed, and everything in the exhibition hall was cleared out. Left empty and silent, the site stood abandoned, waiting for a new lease of life.

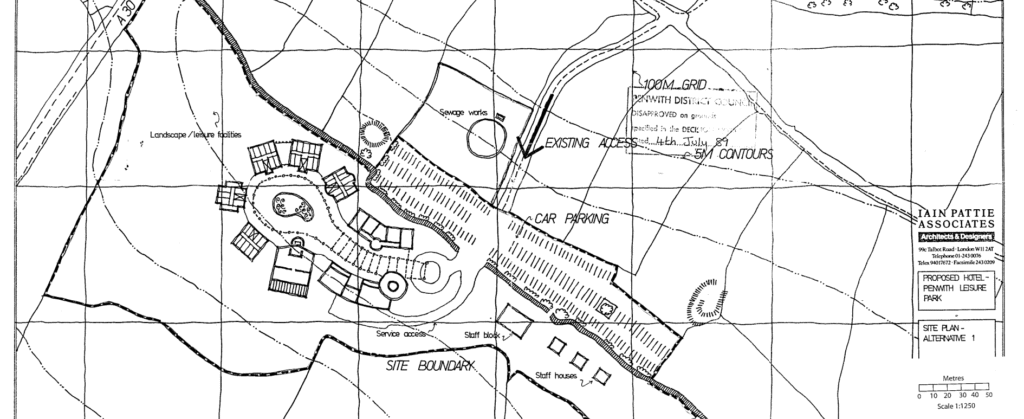

At some later point the park was acquired by the Ugandan-owned Virani Group, who at the time controlled several hundred UK pubs along with dozens of hotels and supermarkets. In 1988 they applied for outline planning permission to build a 125-bed hotel and a 300-person conference facility on the land. The application was refused.

In 1990, a large group of New Age travellers moved onto the grounds and took up residence. The parish council, who referred to them as bus people, voiced concern over their arrival but acknowledged that little could be done “in the face of indifference by the absentee landlords.”

The travellers stayed for around three years before they were kicked out. The site was in terrible condition and any remaining structures were later demolished. The land was cleaned up and today lies vacant and overgrown. According to a forum post in 2010 the site is “used by teenagers getting drunk, people on moto-X bikes and old people walking dogs.” If you live in the area and could get in to take some photos of what it looks like today, we’d be happy to post them here.

What happened to all the stuff?

All four locos from the miniature railway still survive today. The steam engine Trevithick, along with two of the carriages, spent some time on the Watford Miniature Railway during the 1990s. But the two steamers were later reunited, and they’re both now at the Royal Victoria Railway near Southampton. The old Shillingstone/Age of Steam turntable remains in use at Watford. The two diesels are now in private ownership.

As for the old fairground rides, some were later returned to Hollycombe, which is now operated by a charitable trust. This includes the Razzle Dazzle, the Steam Swings. and the Steam Yacht. Others were sold elsewhere, for example the merry-go-round (Gallopers) is now in Australia. I’ve no idea what happened to the model railways and museum displays.

Where exactly was the park?

My personal story

I visited Age of Steam around 1981 while on a family holiday in Cornwall. At the time, I was a train-crazy 13-year-old who had pestered my parents into taking me there. Yet, despite all my enthusiasm, I came away a bit underwhelmed. There simply wasn’t enough to do, and I think that was one of the main reasons the park ultimately failed – you could do it all in about an hour. Even the train ride, which was advertised as being a mile long, felt a bit boring, and it felt shorter than other “mile-long” railways I had ridden. I just wasn’t too impressed.

Fast forward to 1990, I found myself back in Penzance. I’d heard the park had closed so I decided to call in and see what remained. Driving through the old main entrance in my Austin Metro rental car, I made my way down to the exhibition hall. As expected, the place was very overgrown, but the reality was even more shocking. The outer walls of the main building were covered in graffiti, every window was smashed, and the grounds were littered with junk – old fridges, piles of rubbish, and burnt-out cars, some overturned on their roofs. It felt like I had stumbled into a post-apocalyptic film set.

Looking back, they probably assumed I was someone official from the council. Perhaps if I’d taken the time to explain what I was doing then things might have turned out far less intimidating – but in that moment, running away felt like the best option.

The photos and video below were taken by my mum during our 1981 visit. Unfortunately the video is pretty poor quality.

The video below was shot on Super 8 film and the transfer is very bad quality….

We’d love to hear your stories and memories of the park. Please feel free to leave a comment below.